By Colin Y. Sewake

In Okinawa, the word yuimaaru expresses the spirit of cooperation. A perfect example of yuimaaru is the long-standing bridge that the Okinawa-Hawaii Kyokai (OHK) has created between Hawaiʻi and Okinawa since 1966. At some point after the Battle of Okinawa in 1945, Okinawans started to travel abroad, including to Hawaiʻi, for college education. OHK provided yuimaaru for students who were expected to be leaders upon returning home to rebuild the community. OHK further supported Hawaiʻi Uchinānchu (Okinawans) at large by supporting the Hawaii United Okinawa Association (HUOA).

How I got involved

One thing I should share about myself is that I am not Uchinanchu and, for 23 years, I grew up in Hawaiʻi. I didnʻt know much about Okinawa and had never heard of HUOA. For 21 years, after arriving in Okinawa in 1994, I did not engage with the Hawaʻi Uchinānchu community.Then in January 2016, I reached out to the Yomitan Club of Hawaiʻi, one of 50 HUOA charter clubs. I wanted to offer support to the descendants of the immigrants who came from Yomitan – the village where I resided.

During a trip to Hawaiʻi that year in July, I visited the Hawaii Okinawa Center (HOC) in Waipahū and met HUOA’s then-Executive Director Jane Serikaku, further expanding my Hawaiʻi-Okinawa network. Upon returning to Okinawa, I was introduced to the director of the Okinawa Prefectural Library (OPL) and Genealogical Reference Services Team Leader, Hiroaki Hara; I volunteered to support their booth at the 6th Worldwide Uchinānchu Festival (WUF) in 2016.

In the months leading up to the 6th WUF, I also met OHK President Chōkō Takayama, Vice President Asami Ginoza, and Director Masaji Matsuda, and many others who were members of OHK. When they learned about my Hawaiʻi and Okinawa background and recent volunteer efforts, they quickly recruited me as an assistant director. I followed them around. My eyes were opened to Okinawa culture, history, and people, and the strong connections between the two island communities.

A History Behind “The Bridge”

I’ve been on a Battle of Okinawa tour before and saw footage broadcast on Okinawa news regularly, but I never knew about the Okinawan Prisoners of War (POW) who were taken to Hawai’i and interred there for a year and a half, nor did I know about the post-war relief effort of Hawai’i Uchinānchu who sent 550 pigs, 750 goats, clothing items, and medical and school supplies to Okinawa. Additionally, I was surprised to learn some of the songs we sang in Sunday church service were actually traditional Okinawan songs with the lyrics revised. As I became more and more involved, I got to know individuals and groups from both Hawai’i and Okinawa.

Yuimaaru Over the Years

Hawaii Okinawa Center in Waipi’o, O’ahu

For the 1990 opening of the Hawaii Okinawa Center in Waipi’o, Ginoza led an effort to send 75,000 akagawara (red roof tiles) as well as seven roofing experts and the cement and other supplies needed to install those tiles. The two large shīsā which stand in front of the Legacy Ballroom were also presented as gifts from Okinawa. According to Ginoza, the original plan for the HOC was for the construction of an American style building. The sentiment on the Okinawa side was: if that much effort and funding was being put into the building, it should have an Okinawan look to it. The design was revised midstream to incorporate Okinawan style roofing using the akagawara. The other reason for sending the akagawara – which were donated using funds raised from town offices, businesses, groups, and individuals – is that Okinawa wanted to send their heartfelt reciprocation, or ongaeshi, for the postwar relief effort of 550 pigs and other items that were sent from Hawai’i.

World Uchinanchu Festival in Okinawa

During the 5th World Uchinanchu Festival (WUF) in 2011, OHK coordinated a speech presentation and welcome party for Hawaiʻi Gov. Neil Abercrombie in Naha, with 450 people in attendance. In 2013, OHK and FM21 (76.8 FM) hosted a fundraiser for HUOA at Tedako Hall. Two years later, in 2015, when the first U.S. governor of Uchinānchu descent, Gov. David Ige, visited Okinawa, OHK organized a lecture presentation for him, escorted him to hakamairi (a grave/tomb visit) in his ancestral hometown of Nishihara, and planned a welcome party attended by 500 Okinawans. In the same year, Honolulu Mayor Kirk Caldwell was also warmly received in true Okinawan spirit.

When I joined the Hawaiʻi-Okinawa community in 2016, the excitement surrounding the 6th WUF gradually built up over the coming months. That year, FM Yomitan Radio (78.6 FM) in Okinawa held a joint broadcast every Monday with KZOO Radio (1210 AM) in Hawaiʻi to coincide with HUOA’s weekly radio show on Sundays. Occasionally, I accompanied Takayama, Ginoza, and Matsuda to the FM Yomitan studio to join the conversations about topics related to our two island communities.

During the 6th WUF, several OHK members marched alongside the Hawaiʻi contingent, led by past HUOA presidents holding the main banner, in the opening parade on Kokusai Street in Naha. This marked the beginning of the festival, which welcomes Uchinānchu descendants back to their ancestral homeland every five years. Later that week, approximately 500 attendees greeted Gov. Ige at a welcome party hosted by OHK.

While the five-day event was underway, I volunteered as a translator at OPL’s first genealogical reference services booth. Here, Uchinānchu descendants from around the world could submit their immigrant ancestors’ names, birthdates, and hometowns in hopes of finding information in the library’s immigration database and records. Even after the 6th WUF concluded, this service continued, resulting in several successful cases where descendants not only discovered information about their Okinawan relatives but also met them in person.

Closure For POWs

I wasn’t sure what other events would follow the Taikai, but then I received a call from Matsuda, who told me that Takayama wanted me to join the Former Okinawan POW Memorial Service Committee. Over 3,100 Okinawans who served in the Japanese Imperial Army were taken as POWs to Hawaiʻi, where they spent a year and a half at internment camps in Honoʻuliʻuli and Sand Island. Twelve of these POWs died of natural causes during their internment. Hikoshin Toguchi, one of the former POWs, wanted to locate the disposition of their remains, as he had heard they were returned to Japan, but it could not be confirmed if they ever made it back to Okinawa. He hoped to at least hold an ireisai (memorial service) in Hawaiʻi, even if the disposition of the remains could not be verified.

A committee of 12 members was formed, including four of us from OHK. Takayama and Toguchi served as co-chairs, with Ginoza as co-vice chairman, Matsuda as director, and me as assistant director.

After months of planning and coordination with HUOA, the committee and an Okinawan contingent of approximately 85 members—including some relatives of former POWs—accompanied Toguchi and fellow former POW Saneyoshi Furugen to Hawaiʻi in June 2017. The first stop was at a cemetery on Schofield Barracks, where the remains of the 12 POWs were originally interred before being exhumed (their final disposition remains unknown). National Living Treasure Chōichi Terukina performed two special songs on the sanshin (Okinawan three-stringed instrument).

The next stop was Honoʻuliʻuli, where the two former POWs revisited the place they had been held 72 years earlier. Many tears flowed as flowers were offered at a small stream, and Brandon Ufugusuku Ing performed a song on his sanshin. Additional stops were made at Hickam Air Force Base, where Toguchi shared stories of working there during the internment, and at R.K. Oshiro Doors on Sand Island, where a small service was held at the exact location where the POWs had been detained.

The ireisai was held afterward at Jikoen Hongwanji Mission in Kalihi, attended by many Uchinānchu from the Hawaiʻi community. Terukina Sensei and members of the Ryūkyū Koten Afuso Ryū Ongaku Kenkyū Chōichi Kai Hawaiʻi Chapter performed during the service. Later that evening, a konshinkai (social gathering) dinner was held at the Pagoda Hotel.

At both the ireisai and konshinkai, Terukina Sensei performed with a sanshin that held deep historical significance. During their internment, the POWs used large empty cans, lumber, and wire to make kankara sanshin. When Hawaiʻi Issei (first generation) Kamesuke Kakazu heard about the POWs, he presented his personal sanshin to his relative who was a POW. After the internment ended, the instrument returned to Okinawa and remained in the family. Seventy-two years later, the POW’s nephew, Susumu Kakazu, brought it back to Hawaiʻi to be played once more by Terukina Sensei, creating a poignant connection between past and present.

Hawaii Okinawa Plaza

From 2013, Former OHK President Akira Makiya and later Ginoza led an initiative to raise support for the Hawaiʻi Okinawa Plaza (HOP), an income-producing property that was being built to ensure the sustainability and long-term goals of HUOA. In the beginning, visits were made to Okinawa town mayors, businesses, and various organizations to appeal for support for the HOP. I later joined Takayama, Ginoza, and Matsuda in 2018 as they re-visited those groups to collect donations and thank them for their support. Over 430 people from Okinawa traveled to Hawaiʻi for the HOP opening ceremony in 2018 followed by a presentation of ¥120,000,000 (approximately $1M) to HUOA.

As I followed these individuals, I was struck by how deeply they and others in the Okinawa-Hawaii Kyokai (OHK) community supported Hawai‘i’s Uchinānchu. Ginoza shared a poignant memory from when he was 10 years old during the war, walking barefoot. When relief supplies arrived from Hawai‘i, he explained, “We couldn’t be picky. We had to use whatever we were given, even if the clothes, like aloha shirts, were too big.”

Takayama’s first visit to Hawai‘i in 1962, as a student at the University of Hawai‘i East-West Center, also left a lasting impression. During a 40-day Greyhound tour across the U.S. mainland, he marveled at the higher standard of living enjoyed by Hawai‘i’s Uchinānchu, which he described as “ten times better” than what Okinawans experienced at the time. His curiosity led him to seek out Issei (first-generation immigrants) to learn about their lives and hear their powerful stories of immigration and perseverance.

Overwhelming Contributions to the Maui Strong Fund

Recently, Okinawa-Hawaii Kyokai (OHK) raised over ¥90,000,000 (approximately $575,000) for the Maui wildfires through the Chimugukuru Project. According to a Maui News article from August, in collaboration with OHK, the Hawai‘i United Okinawa Association (HUOA) donated $672,076.98 to the Maui Strong Fund, which is organized by the Hawai‘i Community Foundation (HCF). This substantial contribution was made possible through a fundraising campaign that included donations from Okinawan residents, businesses, and elected officials. The effort embodies the spirit of yuimaaru—the Okinawan tradition of communities coming together to support one another, especially in times of need. The Maui Strong Fund has received a total of $196 million in donations from various sources to assist with the island’s recovery after the devastating wildfires.

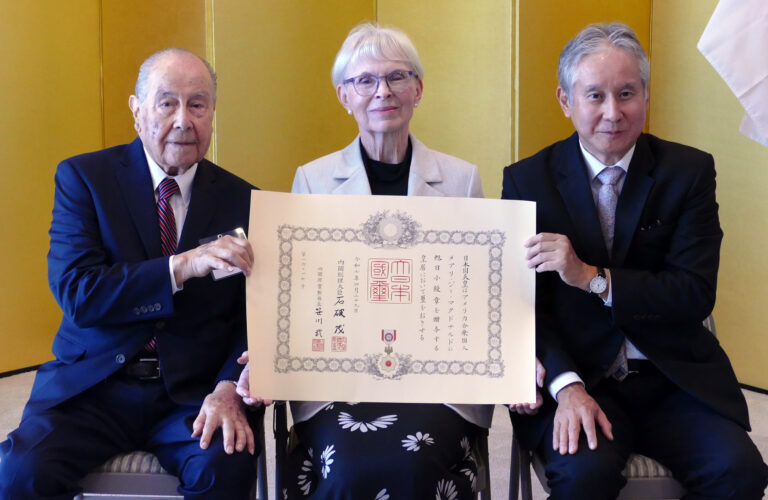

OHK’s support for HUOA, under the leadership of President Takao Kadekaru, continues today, as it has for many years. This includes coordinating office visits during the annual HUOA Leadership Aisatsu Visit, hosting kangeikai welcome parties, and greeting Hawai‘i Uchinānchu visitors upon their arrival at Naha Airport. The strong ties between Okinawan Uchinānchu and Hawai‘i Uchinānchu remain vibrant nearly 125 years after the first immigrants arrived in Hawai‘i.

Current Hawaii Okinawa Kyokai President Takao Kadekaru. (Photo courtesy of Colin Sewake)

About the writer:

Colin Y. Sewake, originally from Wahiawā (Leilehua 1989, University of Hawaiʻi 1994), is a retired Air Force officer and resides permanently in Yomitan Village, Okinawa. Married to the former Keiko Yamakawa of Okinawa City, they have two adult children. Colin was a columnist with the Hawaiʻi Herald from 2017 to 2023 and continues to share stories from Okinawa via the San Times. He spends most of his free time volunteering for and strengthening the relationships between the Hawaiʻi and Okinawa communities and is also a board member with Special Olympics Nippon – Okinawa.