Editors’ Note:

We acknowledge that the U.S. Army has restored the 442nd Regimental Combat Team’s section to its website after its recent removal, reportedly due to changes in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) policies. However, this history should never have been erased in the first place. The 442nd RCT, composed primarily of Japanese American soldiers, is one of the most highly decorated units in U.S. military history. Their legacy is not just one of resilience, sacrifice, and patriotism—it is an undeniable part of American history.

These brave soldiers were segregated not because of their abilities, but because of the prejudices of their own government. Yet, they fought with unwavering courage, proving their loyalty to a country that had questioned their place in it. Their history is our history. It is American history. The more we acknowledge and understand this past, the better equipped we are to prevent history from repeating itself. Recognizing their sacrifices reinforces the vital truth that we must stand together as one nation, united in the pursuit of justice and equality.

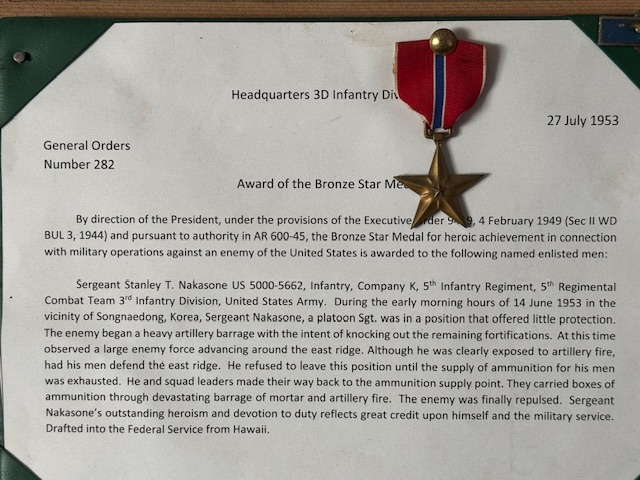

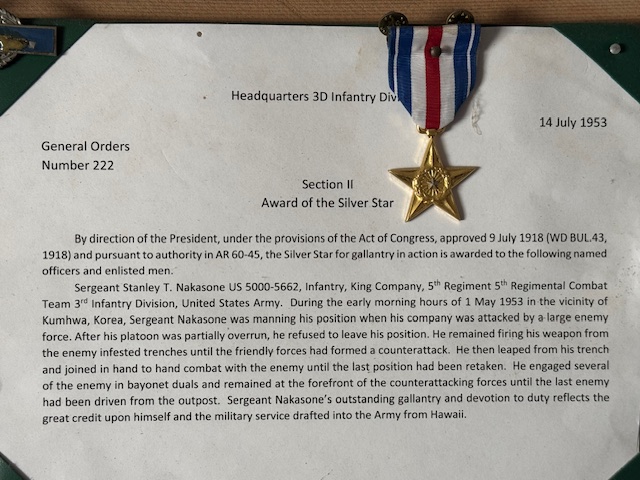

San Times stands firmly with our AAPI community and all who work to ensure that these stories are never forgotten. We remain committed to preserving and sharing the legacies of heroes like Stanley Nakasone, so that their contributions continue to inspire future generations.

By Dan Nakasone

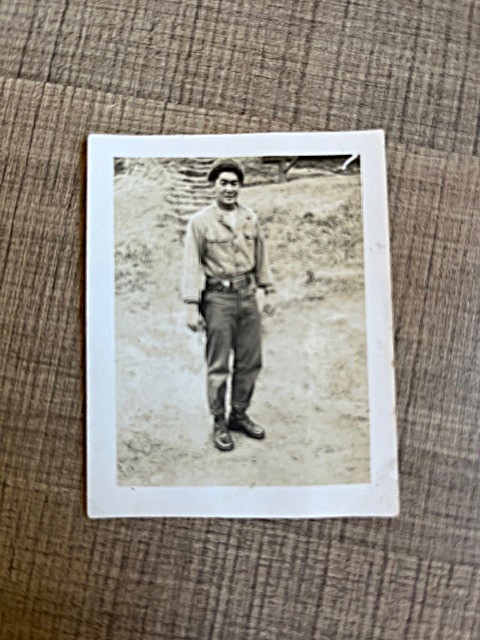

I first met Stanley Nakasone about 20 years ago while volunteering as a ranch hand at the North Shore Cattle Company, nestled in the foothills of the Koʻolau Mountains. Stanley, his son Kalani, and his longtime friends Augie and Pablo were regulars at the ranch, often hunting wild pigs in the area.

Back then, our interactions were brief—friendly conversations in passing—but I never got to know him well.

That changed on the morning of December 7, 2024, when I unexpectedly crossed paths with 93-year-old Stanley during a walk in Wahiawā, where we both live. As we talked, he shared a story about what he, his brother Harry, and their friends witnessed on December 7, 1941—the day Pearl Harbor was attacked. His vivid recollection piqued my curiosity, leading me to learn more about his extraordinary life.

From his humble beginnings in a small pineapple plantation camp to his service as a decorated Korean War veteran, Stanley’s journey is one of resilience, courage, and history brought to life.

This is his remarkable story.

“The Best Life” at Kemoʻo Camp

Kemoʻo Camp was established around 1920 as one of several plantation camps operated by the Hawaiian Pineapple Company (now Dole Food Company) between Wahiawā and the North Shore. Situated next to Poamoho Gulch, about a mile past present-day Poamoho Camp outside Wahiawā, its entrance was a half-mile dirt road off Kaukonahua Road—known in those days as “Government Road.”

Stanley grew up in a small three-bedroom house in Kemoʻo Camp with his parents, Seiichi and Kana, and his seven siblings. “Ten of you in that house?” I remarked.

“We had enough room,” Stanley replied matter-of-factly.

Like many plantation homes of the era, their rustic “board and batten” house was simple, with a single bare light bulb hanging in each room. Toilets were outhouses, and the community bathhouse featured large redwood tubs, called furo in Japanese. A wood-burning stove heated the water, and the men’s and women’s baths were separated by a common wall.

“Everyone was close. Everybody helped each other out. Nobody locked their doors. We ate at each other’s houses, especially on New Year’s Eve, when there was so much good food,” Stanley recalled with a smile. “And people shared—like the Portuguese bread baked in the forno (outdoor brick oven) at the camp.”

Before World War II, the Hawaiian Pineapple Company sponsored Christmas parties and summer picnics for camp residents. During the war years, the children staged Christmas Eve plays on a makeshift stage in front of the baseball backstop, using pineapple boxes as seating. One year, soldiers from a nearby encampment were invited to watch, and they were deeply appreciative. (Kemoʻo Camp 1996 Reunion Booklet)

“That was the best life. Country life,” Stanley said. “We had chores every day after school—watering the garden, feeding the animals. We had pigs, chickens, ducks, and rabbits. But after that, we’d all meet at the ball field to play baseball, basketball on a dirt court, or football. Sometimes, we’d head to the clubhouse to play ping pong or cards. Other days, we’d go down to the gulch and fish in the stream—catching grayfish and ‘o‘opu (Hawaiian freshwater goby). The grayfish tasted good, and the ‘o‘opu was even better fried.”

But life wasn’t all play.

“At twelve, we started working—picking pineapples in the summers, on weekends, and holidays,” Stanley said. “Eight-hour days. Twenty-five cents an hour. That was big money.”

Kemoʻo Camp on December 7, 1941

Stanley was 12 years old when he and his younger brother, Harry, were playing with friends at the ball field. Suddenly, a low-flying plane with red zeros on its wings roared overhead, so close that they could see the pilot laughing at them.

“We thought we were going to get shot—bullets were hitting the ground,” Stanley recalled. “We were so scared, we ran. My brother was shaken up for days after that.”

The pilot continued on, strafing the camp’s warehouses with machine-gun fire. Later, Stanley learned that a stray bullet had killed a young boy in the camp.

They watched as a U.S. aircraft engaged the Japanese plane, shooting it down in a pineapple field between Kemoʻo Camp and Brodie Camp 4. “We ran toward Brodie Camp 4 and saw the plane catch fire, with the pilot and gunner still inside,” Stanley said. “We also heard that a man was killed by a stray bullet while he was in his kitchen at Brodie Camp 4.”

Not long after the attack, FBI agents arrived at Stanley’s home to question his father. “My brother Harry had been talking at school about playing with a sword, and his teacher reported it to the FBI. They came to our house and demanded to know where the weapons were. My mother was all shook up,” Stanley said.

The so-called “sword” Harry had mentioned was just a piece of wood. But that didn’t stop the agents from searching their home and confiscating their father’s sanshin—a traditional Okinawan musical instrument with snakeskin—and their family’s radio.

The camp’s manager, Zensuke Kurosawa, was also arrested by federal agents and sent to the Santa Fe internment camp in New Mexico.

Never Forget the “Forgotten War”

The Korean War, often called the “Forgotten War,” began on June 25, 1950, and officially ended on July 27, 1953. The United States fought alongside troops from other United Nations member nations, while North Korea received support from China and the Soviet Union. Chinese troops fought directly, and Russian forces trained and equipped the North Korean People’s Army.

On July 22, 1950, the U.S. Army’s 5th Regimental Combat Team (5th RCT), stationed at Schofield Barracks on Oʻahu, deployed to Korea with 3,200 soldiers—including a regiment of Hawaiʻi boys. Civilians lined the roads outside the main gate, shouting, “Aloha! Good luck, and Godspeed!” along with, “Give ‘em hell!” (Hills of Sacrifice – The 5th RCT in Korea).

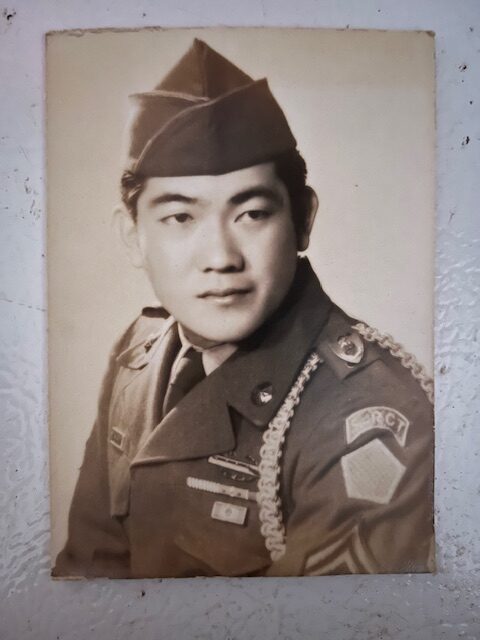

Stanley wasn’t among that first group. He was drafted at 19 and later deployed, serving alongside two other Wahiawā men—Santiago “Sandy” Bunda and Hibbert Manley. All three became sergeants in the 5th RCT, with Stanley rising to platoon sergeant, responsible for 48 men.

The 5th RCT was known as a “Bastard Outfit,” meaning it had no permanent divisional headquarters. It was often sent into the fiercest battles, tasked with breaking through heavily fortified Communist positions (Hills of Sacrifice).

“I remember the bitter cold,” Stanley said, shaking his head. “I got frostbite on both legs. A lot of our boys did. But we just kept fighting.”

The Army didn’t provide enough winter clothing in large quantities, forcing U.S. soldiers to scavenge whatever they could to stay warm. Some even wore captured North Korean winter uniforms (Hills of Sacrifice).

Purple Heart

During battle, Stanley was struck in the leg by shrapnel from a grenade.

“I told medic Mits Imai to patch me up, and I kept fighting,” he recalled.

Only recently did he learn that fragments of that shrapnel remain in his leg to this day.

Reflecting on those battles, Stanley shared, “We fought the Chinese. The North Koreans were pau (finished) already. The Chinese would sound their bugles and whistles as they charged, yelling. They were crazy, like they were on drugs. They had very few weapons. The first wave carried old rifles, and the second wave would pick up the weapons from those who were killed.”

During hand-to-hand combat, Stanley chose not to use a bayonet. “I used the butt of my rifle,” he said. “We didn’t know if we were going to die or what—we just kept fighting. The saddest thing was seeing men in my platoon die.”

Psychological warfare was another enemy tactic. “They were in a field across from us, and they would play Christmas music to make us homesick.”

Stanley and his unit spent most of their time on the frontlines. “No rest,” he said. But for those who survived, the war eventually ended.

“When we were leaving Korea, the Army band played Aloha ʻOe, I’ll Remember You, and Hawaiʻi Aloha,” Stanley recalled. “I don’t know if I was happy or sad because so many men from Hawaiʻi were left behind.”

The Korean government estimates that more than 450 soldiers from Hawaiʻi were killed in action during the Korean War. Hills of Sacrifice states that the Territory of Hawaiʻi suffered the highest per capita casualty rate of any U.S. state or territory during the war.

The soldiers of the Hawaiʻi regiment took pride in their unique cultural and ethnic diversity (Hills of Sacrifice). They were also among the most highly decorated, including Herbert Kailieha Pililāʻau of Waiʻanae—the first Hawaiian to receive the Medal of Honor.

The bravery of Hawaiʻi’s Korean War soldiers echoed the legendary heroism of the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team of World War II.

As Wahiawā native Hibbert Manley put it in Hills of Sacrifice:

“Go for broke, brah.”

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Like countless other veterans who faced the horrors of war on the frontlines, Stanley suffered from PTSD.

“The VA (Veterans Administration) provided therapy sessions at Tripler Hospital where we talked about our war experiences,” he recalled. “We could go twice a week for what I called ‘Bull Sessions.’ Up to sixty local Korean War vets would show up, including Sandy Bunda and Hibbert Manley.”

For many veterans, these sessions were a crucial space for camaraderie and healing. Unfortunately, they came to an end with the onset of COVID-19.

Closing Reflections

The lingering effects of war extended beyond PTSD. Stanley also lost the ability to drive due to the frostbite he suffered in Korea—he has no feeling in both feet.

Despite the emotional and physical scars, Stanley built a full and meaningful life. With his wife, Setsuko, he raised a family and found joy in the simple things he loved—fishing and hunting with lifelong friends. Now, at 93, he has outlived those closest to him.

“All I have now are memories,” he said.

I feel deeply fortunate that Stanley, a nisei (second-generation Japanese American) soldier, shared his incredible life stories with me. The book The Greatest Generation often refers to those who fought in World War II and those who supported the war effort on the home front. But the men of the 5th Regimental Combat Team and the other American soldiers who fought in the Korean War deserve just as much recognition.

The Korean War should never be forgotten.

Dan Nakasone is a Sansei Uchinanchu from Wahiawā. He is a marketing and advertising professional and was a producer/researcher for PBS’ award-winning food and culture series, Family Ingredients, which is based in Hawai‘i and hosted by Chef Ed Kenney.