A Moment of Recognition

When local photographer Alison Uyehara heard her name announced at the Downtown Art Center this past February, surprise gave way to a rush of emotion. The recognition—one of just two artists honored among dozens of exhibitors—felt surreal. It was as if every seemingly random experience in her life had converged into this moment, each coincidence quietly leading her to the story she was meant to tell.

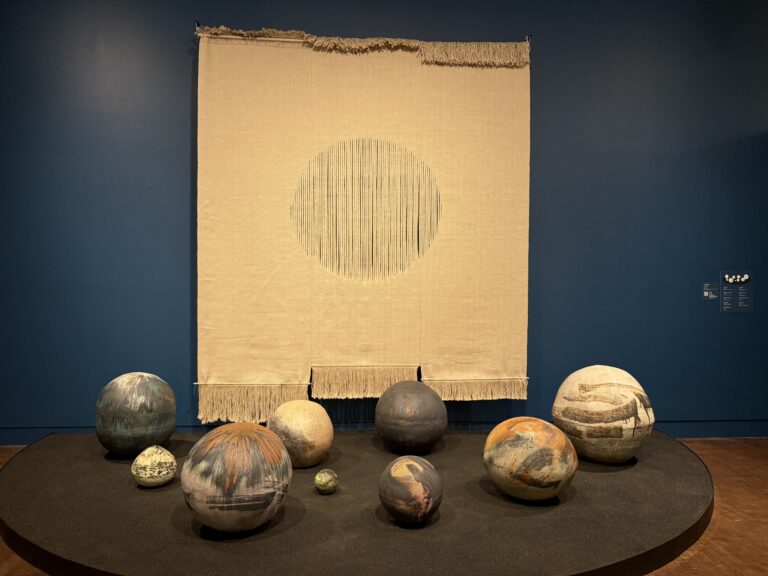

Her exhibit was understated but powerful: two photographs that invited viewers to pause, ask, and listen. Those who did found themselves transported through Uyehara’s lens to Hunt, Idaho, the site of the Minidoka concentration camp, where more than 13,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during the early 1940s.

The name Minidoka, derived from Sioux or Shoshone origins, is said to mean either “spring of water” or “broad expanse.” The vastness of the land reflected the latter, but Uyehara found the “spring of water” in something else—the quiet endurance and gaman of those who lived there. Her pilgrimage to Minidoka, captured through her award-winning photographs, was made possible by a six-month sabbatical in 2023—a journey that changed both her work and her worldview.

The Artist and Educator

As a photography instructor at her alma mater, ʻIolani School, Uyehara has spent years refining her craft and guiding students to find their own creative voice. After earning her degree from Washington University in St. Louis, she began her professional photography career in Missouri before returning home to Hawaiʻi in 2003 to join the ʻIolani faculty.

Her sabbatical became a time of renewal. Through courses in the University of Hawaiʻi system, she studied under acclaimed photographer Franco Salmoiraghi, whose final project—a photo book—later became an assignment she passed on to her own advanced students. For her own project, she chose a subject close to her heart: her grandmother.

From Scratch: A Family Story

Her grandmother, Mary Yemi Nakagawa (née Sasaki), was a Nisei from Bainbridge Island near Seattle—an avid golfer, skilled in shishu (Japanese embroidery), and a talented cook. Her grandfather, also a Nisei but a Kibei, had studied in Japan before returning to Seattle, and thus spoke and wrote Japanese fluently.

Initially, Uyehara considered including her grandparents’ incarceration experience in her photo book, but the topic proved too broad for the course’s timeframe. Instead, she focused on her grandmother’s early adult years—her schooling, marriage, and life leading up to internment.

She titled the book “From Scratch.” The name honored her grandmother’s ability to cook anything from scratch while symbolizing her grandparents’ resilience—rebuilding their lives after incarceration, starting over from scratch. Uyehara plans to continue their story in a second and possibly third volume, exploring the internment years and their aftermath.

A Summer That Changed Everything

The seeds of that story were planted decades earlier. In the summer of 1989, while a college junior, Uyehara made a decision that would later shape her life’s work: instead of returning home to Hawaiʻi for break, she spent the summer with her maternal grandparents in Seattle.

Growing up in Hawaiʻi, Alison was close to her father’s side of the family—her father, Les Uyehara, is well known in the local golf community—but she had rarely seen her mother’s relatives. That summer became her first true connection to her maternal roots.

One evening after dinner, she and her grandmother had a long, heartfelt conversation—one of many to follow—about the family’s experiences during World War II. Mary was among those incarcerated at Minidoka and spoke candidly about camp life, even after four decades.

When her grandfather later passed away, Uyehara was at his side. Before her grandmother’s health declined, Mary gave Uyehara two precious mementos: a handmade shōgi set her grandfather crafted from wooden crates during internment, and a Harmony Tobacco tin—a relic from Camp Harmony, the temporary detention center at Puyallup, Washington, where families were held before being sent to Minidoka. The irony of its name, “Harmony,” was not lost on her.

Paths Converge: Coincidences and Connections

A series of coincidences soon deepened Uyehara’s connection to her grandparents’ story.

At ʻIolani, her journalism class hosted visiting photographer Stan Honda, known for his astrophotography and documentary work. During his visit, he mentioned that his next project would take him to Minidoka—one of the few incarceration sites he had not yet photographed.

They stayed in touch, and Honda later introduced Uyehara to Hanako Wakatsuki, grandniece of Farewell to Manzanar author Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and former superintendent at Minidoka. Around that time, Alison’s cousin—a chef in New York—was featured in a New York Times article about his annual New Year’s pilgrimage to Bainbridge Island, the Sasaki family’s home. Each new connection seemed to pull her more deeply into her family’s legacy.

Pilgrimage to Minidoka

During her 2023 sabbatical, Uyehara traveled across the country—meeting Honda in New York, visiting former professors in St. Louis, and continuing on to Boise, Idaho, accompanied by her aunt and cousin. Her mother had planned to join but was unable to due to mobility challenges.

At Minidoka, Kurt Ikeda, the site’s National Park Service superintendent, and Midori, a summer intern from Oregon, guided them through the grounds. Most structures were gone, but Block 22, where Mary and her mother had lived, still stood. Even more remarkable, Barrack 12, their exact living quarters, remained.

The family walked the makeshift baseball field and the underground root cellar once used to store vegetables and tofu—traces of the lives their ancestors built in the dust. The visit became a deeply personal act of remembrance and healing.

The next day, Uyehara returned alone, carrying her grandfather’s shōgi set, the Harmony Tobacco tin, and family photos. Through her lens, she captured the stillness, resilience, and silence of Minidoka—images that would become the centerpiece of her acclaimed exhibit.

Remembering Through Images

Because cameras were not permitted in the camps, few photos exist from that time. Some formal portraits suggest that limited freedoms were eventually granted, allowing supervised trips to nearby Twin Falls.

Before the war, Uyehara’s grandparents had been members of the Japanese Baptist Church near Seattle’s Chinatown, led by Rev. Emery “Andy” Andrews. The church served as both a spiritual and community center, and Rev. Andrews became an enduring figure in their lives—so much so that he later officiated Alison’s parents’ wedding.

When Uyehara’s grandmother Mary was sent to Camp Harmony, she was pregnant with Uyehara’s mother, who was born during that temporary detention. The family spent the next three and a half years at Minidoka.

After her visit to Idaho, Uyehara traveled to the Japanese Baptist Church, where the current pastor shared archival photographs. Among them, she discovered a picture of her mother as a young child in Sunday School—an image bridging past and present.

Full Circle

For Uyehara, her Minidoka photography exhibit is more than art—it is an act of storytelling across generations. Through her camera, she transforms history into a living narrative of remembrance and resilience.

Her February exhibit marked a milestone in that ongoing journey. This November, she will return to the Downtown Art Center with a new collection, continuing to honor her family’s story and the enduring strength of the human spirit.

About Sharlene Fujisato: Born and raised in Honolulu, she graduated from UH Mānoa with a degree in English and built a diverse career in sales across luxury retail, technology, and funeral services—always guided by the belief that real connection is at the heart of every sale. She’s been working at Hawaii Information Service since 2021. Her husband is a retired Honolulu firefighter, and they have two children. She enjoys traveling, concerts, reading, and swimming.

Alison Uyehara’s Pilgrimage to Minidoka