By Kevin Kawamoto

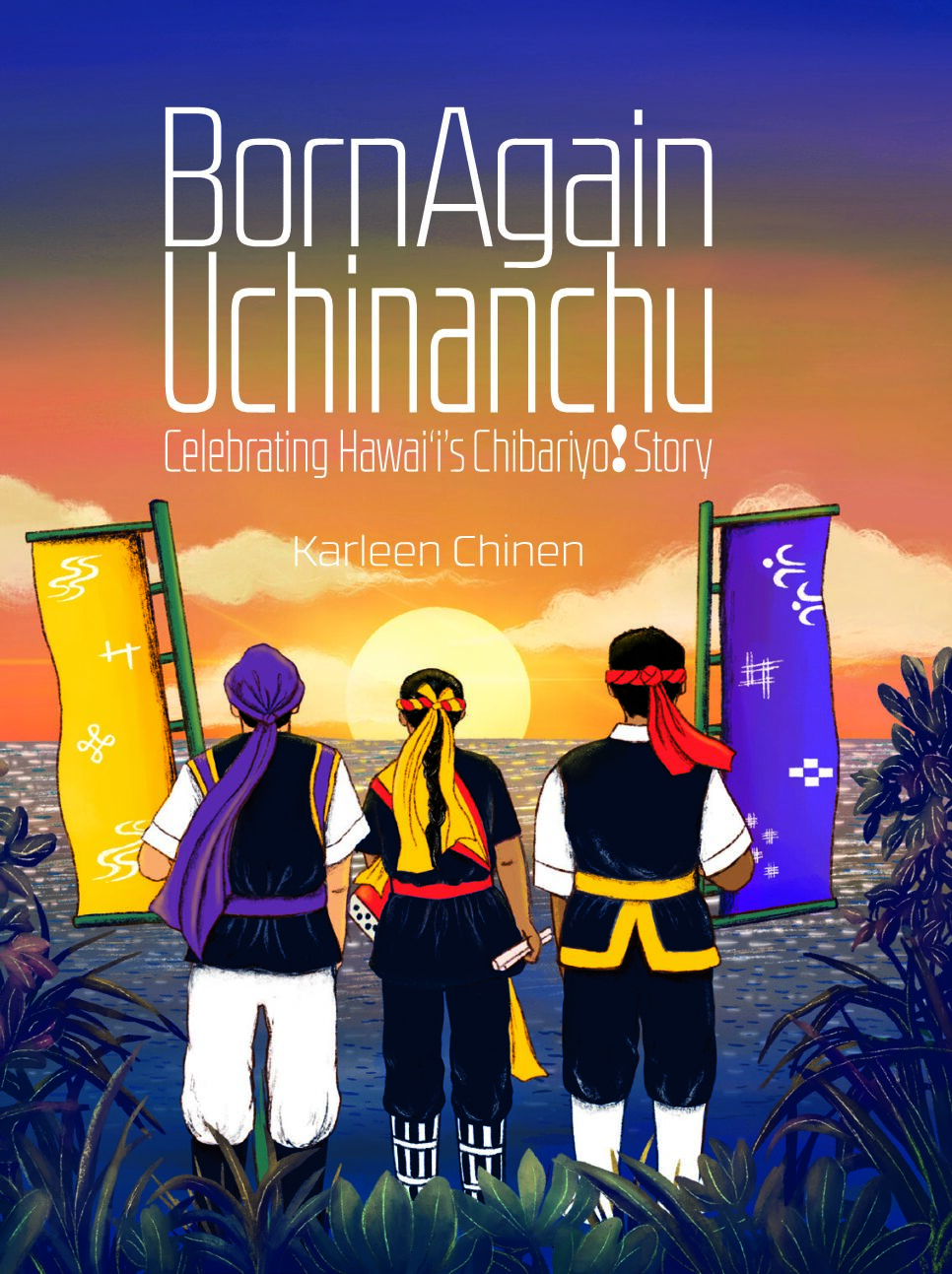

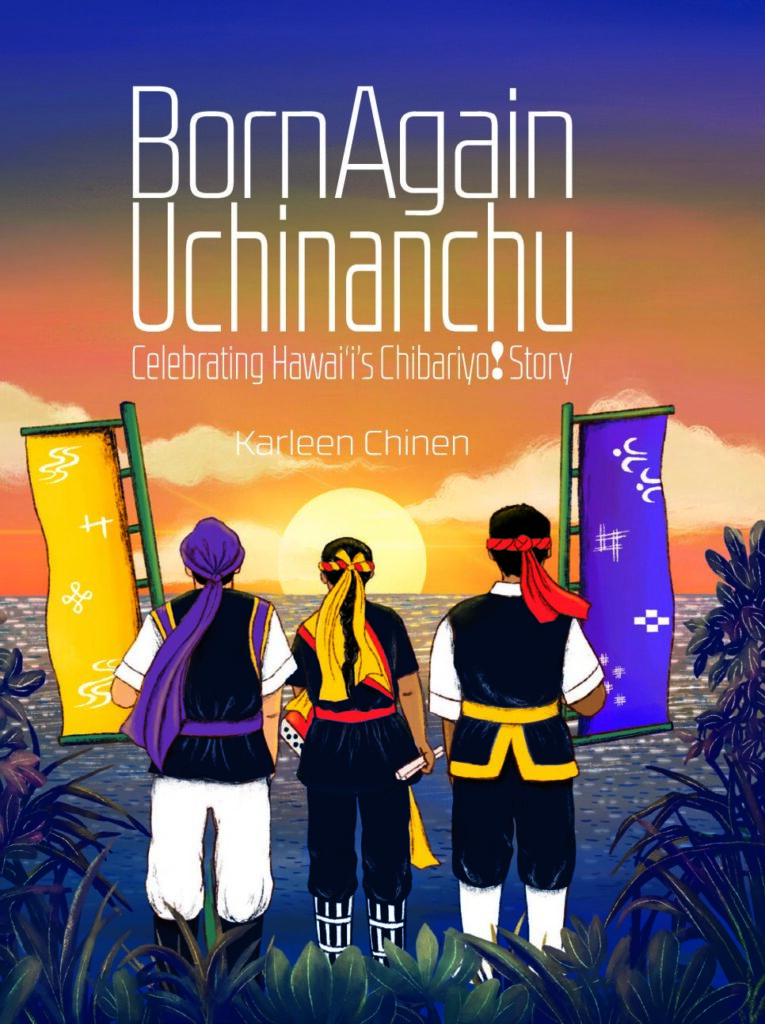

What Ichiro Suzuki has done for Major League Baseball, author Karleen Chinen has done for Okinawan history and culture in Hawaiʻi. The longtime former editor and writer for The Hawaiʻi Herald just hit a homerun with her recent book, Born Again Uchinanchu: Celebrating Hawaiʻi’s Chibariyo! Story, which chronicles a 20-year period between 1980 and 2000 when a freshly inspired group of community members, many of them Sansei or third-generation Okinawan Americans, were moved by the “Chibariyo!” (“Do Your Best!”) spirit to indelibly stamp their Okinawan heritage on the multicultural fabric of Hawaiʻi society.

One of the most vivid examples of this cultural resilience is the beloved Okinawan Festival, now held at the Hawaiʻi Convention Center, which attracts more than 50,000 attendees and involves thousands of volunteers. Old-timers in Hawaiʻi will remember that this annual festival was held at Kapiʻolani Park prior to the Convention Center, but even they may not recall or know that the very first festival was held at Ala Moana Beach Park’s McCoy Pavilion in September of 1982. Every year since then the festival has showcased the best that Okinawan culture in Hawaiʻi has to offer, and a behind-the-scenes look in Chapter 3 of Born Again Uchinanchu describes what it took to get this monumental undertaking off the ground. The chapter is fascinating in that it not only documents, in words and photographs, a seminal event in Hawaiʻi’s Uchinanchu history, but it also gives readers a glimpse into that enviable networking

capacity of Okinawan community leaders, clubs, temples, and other organizations and businesses – especially in the restaurant and food industry – as well as the diverse web of Uchinanchu supporters and allies.

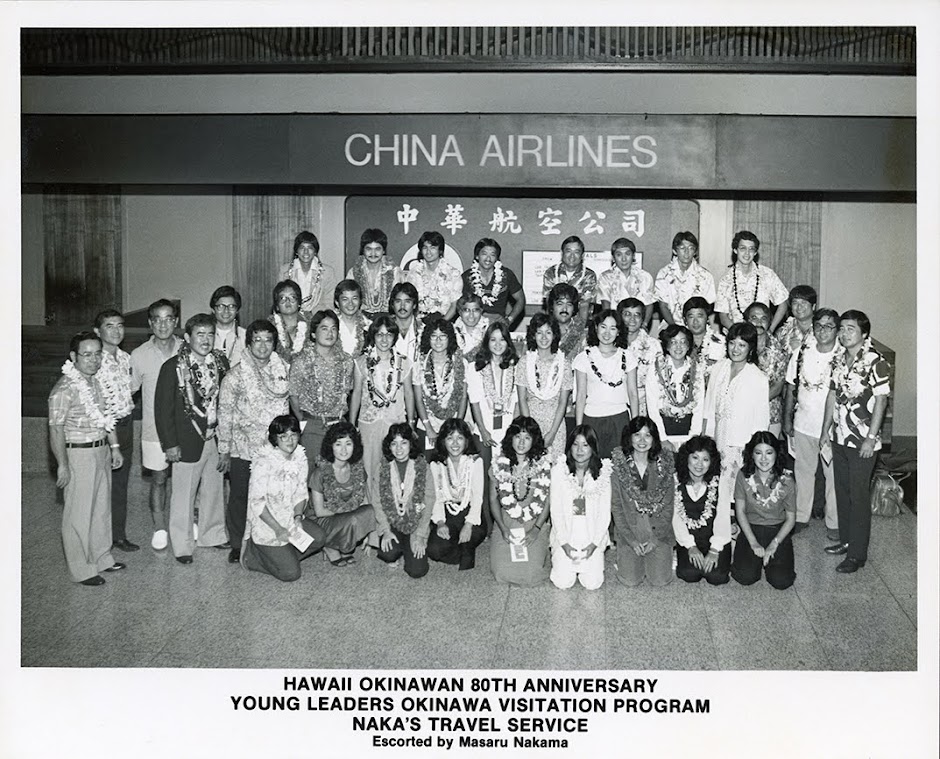

The Okinawa Study Tour

Spearheading the effort to launch the very first Okinawan Festival in 1982 was Roy Kaneshiro, president of the United Okinawan Association of Hawaii (as it was then known, renamed in 1995 to Hawaii United Okinawa Association). Inspired by a study tour to Okinawa in 1980, Kaneshiro and other study tour participants had an opportunity to attend the Naha Matsuri – matsuri means festival in Japanese – where they witnessed first-hand the spirited and festive expression of cultural pride among people with a strong, unified social identity. This ability to celebrate what is good despite a tragic wartime history, the militarization of their homeland, and the social destabilization that accompanies colonization demonstrated an indomitable spirit that refused to be suppressed. Through all this and more, they still proudly asserted their identity as Uchinanchu, a word that conceptually links ethnic Okinawans in Hawaiʻi to those in their ancestral home. However, the Sansei in Hawaiʻi lived their lives two generational steps apart from their pioneering immigrant grandparents. Socialized in American institutions and raised by

Nisei parents who often felt pressure to assimilate into mainstream society, many Sansei had lost touch with their ancestral roots. The study tour was an opportunity not only to reconnect, but to learn. To learn what it truly means to be an Uchinanchu.

By many accounts, the 12-day Okinawa Study Tour was life-altering for the 37 Okinawan Americans (36 Sansei and 1 Nisei) selected for this unique opportunity and supported by a variety of individuals and organizations in both Hawaiʻi and Okinawa. Despite the participants’ excitement to proceed with the tour, there was also some initial apprehension about what to expect. Arrangements had been made for them to meet and homestay for a few days with their Japanese-speaking relatives. Most of the study tour participants did not speak or understand Japanese well enough for a conversation. How were they going to communicate? Would their interactions with the Okinawan people be awkward? Turns out they had nothing to worry about.

“Okinawa residents rolled out the red carpet for their relatives from Hawaiʻi. Everyone –

business owners; prefectural, city, town and village government officials; and everyday

Okinawans – pitched in however they could to welcome home the descendants of immigrant

pioneers,” participant Joyce Chinen writes. They were treated like celebrities wherever they

went. She describes the moments after the group disembarked at Naha Airport.

“Exiting the plane, we were blinded by TV camera lights as we made our way to the

baggage area,” she wrote in an essay a few months after returning from the study tour. “Outside

the glass panes were dozens of people waving, and waving greeting signs. As we made our way

to the VIP lounge, we were presented with shell leis by the Hawaii Club of Okinawa (Okinawa-

Hawaii Kyokai).”

The study tour participants soon realized this experience was a big deal. They met

important government officials as well as everyday folks, had educational lectures, went on site

visits and ate a lot of ʻono (delicious) homecooked and restaurant meals. The homestay

experience was particularly transformative. Somehow communication was not an

unsurmountable barrier, even among relatives who did not speak each other’s language. They

were all Uchinanchu after all, regardless of where they lived or what they spoke, and they let

their hearts and souls do the communicating. The combined aloha and chibariyo spirit was

almost palpable – and it was powerful. Lives were touched, and connections were made that left

a long-lasting impression on both sides. Study tour participants returned home with a deeper

understanding not only of their cultural roots, but also of the innate strengths inherited from their

ancestors and their responsibilities to future generations to “chibariyo!” The book is filled with

the names of people – some better known than others – whose contributions have kept Okinawan culture alive and thriving in Hawaiʻi. The swarms of people staffing the andagi booth year after

year, for example, may not have the spotlight shined upon them, but without them and thousands

of others volunteering many hours of their lives to the Okinawan Festival, the event could not

possibly be the success that is.

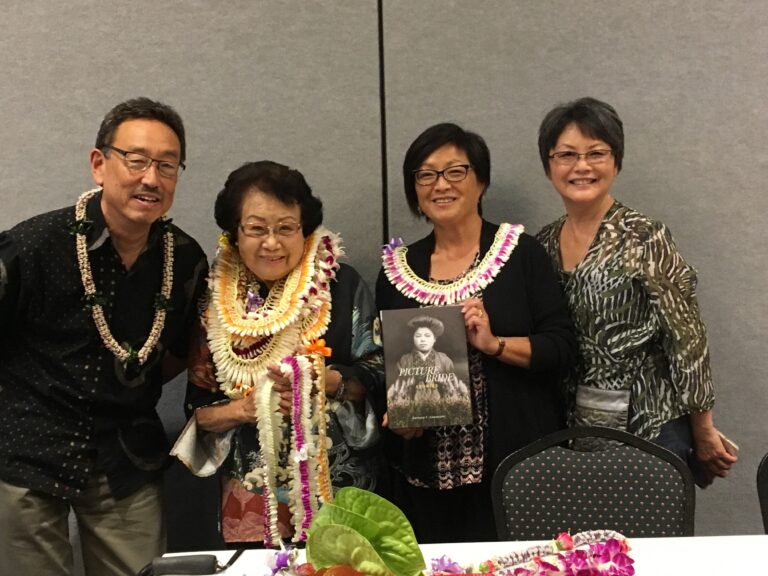

Born Again Uchinanchu is a narratively rich, visually stunning example of meticulous

research and attention to detail. Black-and-white and color photos – many of them magazine-

quality and historically significant – comprise about a third of the book, whose high-end print

quality and elegantly designed layout make it a handsome coffee table display. But this hefty

tome begs to be picked up and handled, perused and digested. Chinen’s prowess as a writer

shines through from cover to cover. Her ability to pull everything together so beautifully

probably stems from her decades as a professional journalist and editor covering a wide variety

of topics related to Okinawans in Hawaiʻi and her direct involvement, as an Uchinanchu herself,

in community events and activities. This book has the intellectual weight of a serious academic

text, but Chinen is no distant armchair scholar far removed from the frontlines of community

engagement. She has been out there at events, notebook in hand, or working the phones. Her

writing style is conversational, inviting and unpretentious – accessible and appealing to multiple

generations from all walks of life. As such, she is a known and trusted voice in the Uchinanchu

community.

In sum, the book consists of 10 chapters, plus a foreword by John Waiheʻe III, former

governor of Hawaiʻi, whose wife, Lynne, is Uchinanchu. The former governor writes about the

time he asked his mother-in-law, Matsue Kobashigawa, what it means to be Uchinanchu. She

responded by raising her right hand and squeezing her middle and index fingers together. After

learning more about the Okinawan community in Hawaiʻi, Waiheʻe said he understood what she was trying to convey to him through this symbolic gesture and provides an explanation at the end

of his foreword.

In the prologue, the late Okinawan American writer Jon Shirota shares vivid childhood

memories – not all of them pleasant — about growing up as an ethnically Okinawan but

American-born kid in rural Maui. Written as a letter to his otōsan, his father, Shirota reflects on

the vicissitudes of a life that encompassed both struggle and achievement. His relations with

some members of the Naichi (mainstream Japanese) community, for example, reveal historical

animosities and hurtful, discriminatory behaviors between the two groups that were more

prominent at one time in Hawaiʻi’s history. Following these sections are chapters that

demonstrate author Chinen’s extensive knowledge about Okinawan history and culture in

Hawaiʻi. The book’s photo credits and the long list of names in the Acknowledgments and

Underwriters sections show just what a community-based project this turned out to be. As the

saying goes, “it takes a village,” and the villagers turned up and put out for this collective effort.

It should not be necessary to note that being Uchinanchu in Hawaiʻi is not just about

festivals and celebrations. During World War II, scores of Okinawan American men answered

the call to duty and served their country – the United States of America – honorably and with

heroic valor. Okinawan Americans have contributed to the economic development of the state

through business and commerce, farming and the arts. They have been educators, public servants

and community leaders of one kind or another. Their contributions to making Hawaiʻi a vibrant

and thriving multi-cultural society have been significant.

Okinawans of other generations have worked together to achieve great things, and these

achievements have been documented elsewhere. The post-World War II effort by Hawaiʻi

Okinawans to help re-start the pig industry in Okinawa prefecture is one such example. For those unfamiliar with the story, Google “pigs from the sea” to learn more. On a smaller yet no less

meaningful scale, Okinawans are known for their close-knit extended families and assorted

cultural clubs and organizations. The yuimaaru spirit of mutual help and cooperation is a

distinctive quality of Uchinanchu relations and the thread that ties the different generations

together.

Finally, no book on Okinawans in Hawaiʻi would be complete today without at least

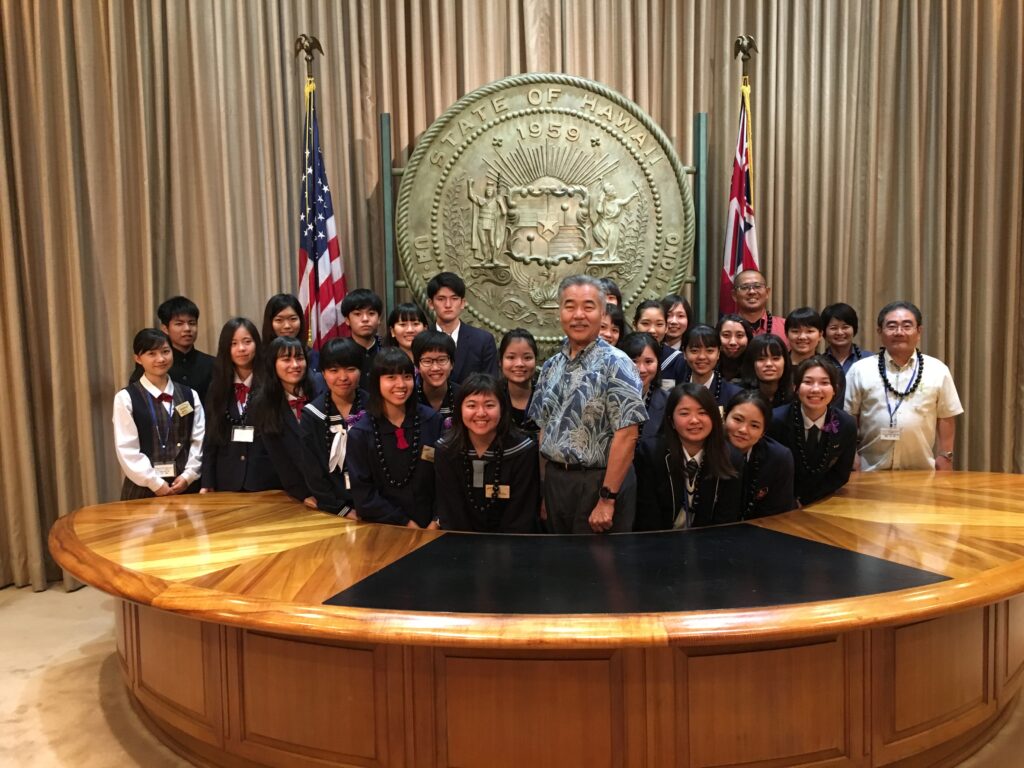

mentioning the historic election of David Yutaka Ige in 2014 as Hawaiʻi’s – and the nation’s –

first governor of Okinawan ancestry. A Sansei, Ige served in both the state House and Senate

before his election as governor. Altogether he enjoyed a 37-year undefeated political career. The

chapter is about some of that, but it is also about Ige’s learning about his Okinawan heritage as

an adult, thanks in no small degree to Governor Waiheʻe, who asked Ige to serve on the 1990

Okinawan Celebration Commission. That experience gave him an insider’s view of what it

means to be Uchinanchu, a question he had not seriously considered up to then. In 2015, he took

his first trip to Okinawa at the invitation of Takeshi Onaga, governor of the prefecture of

Okinawa. Okinawans welcomed and celebrated Governor Ige’s arrival as if he were one of their

own coming back home.

Born Again Uchinanchu is in itself a demonstration of the Chibariyo! (“Do your best!”) spirit that runs through the veins of Uchinanchu who have kept their culture alive and thriving in Hawaiʻi. Chinen shows us where that spirit came from and why it’s so important to keep it going. The book and her life’s work are destined to be a part of the Sansei generation’s legacy to the Okinawan community in Hawaiʻi and should inspire future generations to draw from that Chibariyo! spirit and make a positive difference in their communities – wherever they happen to call home.

This year commemorates 125 years since the arrival of the first Okinawan immigrants to Hawaiʻi on January 8, 1900. Commemorative events and activities will take place throughout the year, and the 43rd annual Okinawan festival is scheduled for August 30 and 31, 2025, at the Hawaiʻi Convention Center. Visit the Hawaii United Okinawa Association’s website at huoa.org for more information. Those interested in purchasing the book, they can e-mail Edward Kuba, kubaedward@gmail.com.

Kevin Y. Kawamoto is a former associate professor at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and

currently works at the UH Mānoa Center on Aging. He has written or co-written a number of

academic textbooks and has been a freelance writer for more than 30 years.