This year’s observance of the 125th anniversary of Okinawan immigration to Hawai‘i has been a celebration of the Uchinanchu community’s progress, but, more importantly, a reminder of the hard lives the early immigrants endured for their families and the generations that followed.

Most of the emigrants in the first group that arrived on the SS China on January 8, 1900, returned to Okinawa at the conclusion of their labor contract. A few decided to seek their fortune on the continental U.S., including the younger brother of Kyuzo Toyama, the man recognized as “the father of Okinawan emigration.” Of the 26 men in the first group, only Chinzen Kinjo remained in Hawai‘i. The families of the thousands of emigrants who followed that first group are now at least five generations old and settled across the globe.

The story of the Japanese and Okinawan immigrant experience is incomplete without recognizing the important role the 21,000 picture brides played in starting families. They came to the Islands to become the wives of men they knew only through the exchange of photos and for what they thought would be only a few years. That became a lifetime for most of them. They now rest in the warm soil of Hawai‘i where their lives are remembered and honored, thanks to the work of the late plantation historian Barbara Fusako Kawakami, who documented their lives of grit, sacrifice and perseverance.

Barbara Kawakami died last December at the age of 103. At her memorial service earlier this year at the Mililani Memorial Park Mortuary, the Reverend Kojun Hashimoto of the Wahiawa Hongwanji Mission, announced the Buddhist name he had bestowed upon her: Shaku Myo-gon. He could not have picked a more fitting name for her. Shaku, Hashimoto-Sensei explained, is the name for Shakyamuni Buddha’s disciple. Myo means “to everyone,” and gon means “word.”

“Even though she passed away, her word is still living,” he said. It lives on in the talks Barbara gave and the books and papers she authored on plantation clothing and the picture bride experience. They are treasures that document an era and a people too often overlooked. Hashimoto-Sensei explained that when a rice plant is growing, its head bends downward, symbolizing humility. “To me, she is a good example,” he said.

It was fitting that Barbara’s service began with a medley of holehole bushi songs sung by Allison Arakawa, dressed in the plantation worker’s outfit that Barbara had created specially for her with fabric given to her by a picture bride. “It was always an honor to sing the holehole bushi for Barbara’s events,” Arakawa said. “She was such an inspiration and I often think of her when I feel defeated. Barbara was testimony to what could be accomplished with passion and perseverance.”

“As I sang at her service, I thought to myself, ‘Barbara would be happy to see her sewn creation one more time.’” Arakawa was 14 years old when Barbara sewed the outfit for her. It carries “the spirit and history of the Issei,” Arakawa said. “It felt right to reunite them as we celebrated her long, amazing life.”

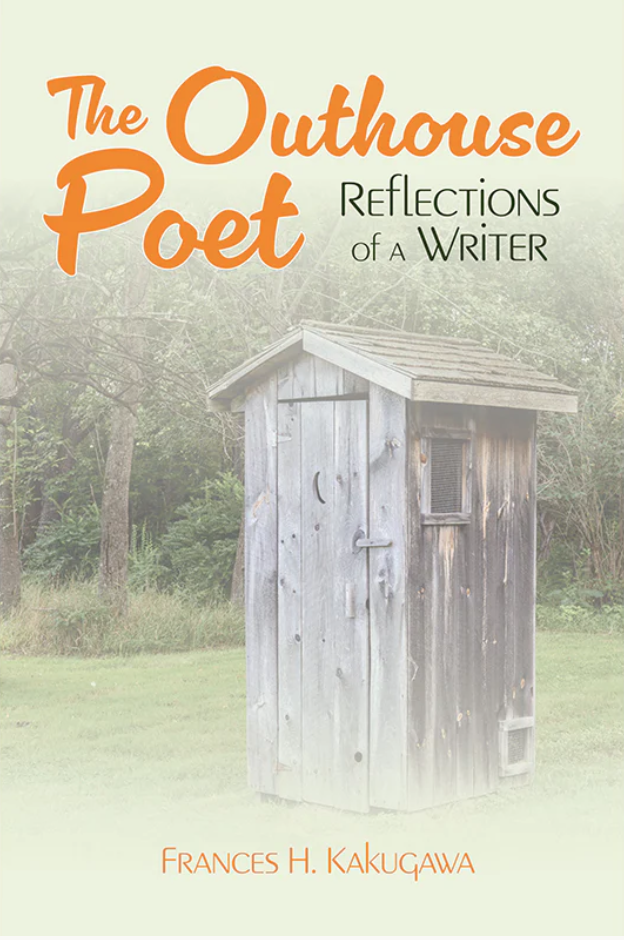

In the preface of Barbara’s first book, “Japanese Immigrant Clothing in Hawaii, 1885-1941,” published in 1993 by the University of Hawai‘i Press, she shared her discovery while researching Japanese immigrant clothing. “… I soon found that my research was taking me on an exciting journey from the Japanese villages to the Hawaiian plantations — a journey that has not only taught me a great deal about the clothing worn by the Issei but also helped me to understand their struggle to survive and the relationship between their old traditions and the new plantation culture.” Her book sparked interest in Hawai‘i’s plantation work clothing and led to the development of exhibitions by the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles and Honolulu’s Bishop Museum — just two institutions of several that Barbara donated her collections of clothing, photographs and other research materials.

Barbara was born in Kumamoto on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu. After immigrating to Hawai‘i, her Issei parents had moved back to Japan with their young family. After only a few months back in Kumamoto, her father had a change of heart and decided that they should all return to Hawai‘i, where opportunities seemed better. Barbara was three months old when their family arrived back in Hawai‘i. Her father worked for Oahu Sugar Plantation in Waipahu, where the family lived. He died at age 63, leaving his wife to raise their eight children. Like many of her generation, Barbara was forced to leave school after the eighth grade to help support their family. For a child who loved school and learning, it was a huge disappointment.

Barbara immediately began taking sewing lessons to become a professional dressmaker. At 22, she married Douglas Kawakami. They had three children — Steven, Fay and Gary. Although Barbara had lived in Japan for only three months, she remained a Japanese citizen until she was naturalized as an American citizen in 1955 after studying for the naturalization test. In 1959, she earned her GED, the equivalent of a high school diploma.

After a 38-year-long career as a dressmaker, Barbara did what she had always dreamt of doing: return to school. Her decision was prompted in part by a conversation with her son, Gary, on the eve of his departure for college on the continent. In the preface of her second book, “Picture Bride Stories,” she recalled Gary asking her, “Mom, didn’t you have a dream when you were young, something you always wanted to do?”

She did. Barbara’s desire to continue her education was as strong then as it had been four decades earlier when her dream of starting high school had been dashed. That fire still burned brightly in Barbara. Now that she and Douglas were empty nesters, Barbara decided to pursue her dream. Douglas didn’t share her enthusiasm at first. In time, he came around and supported her by driving her to appointments with her interview subjects.

At the age of 53, Barbara joined students who were less than half her age in pursuing an associate’s degree at Leeward Community College. She didn’t stop there. She then used her dressmaking experience to pursue a bachelor’s degree in fashion design and merchandising at the University of Hawai‘i at Mänoa, which she received in 1979. Four years later, at age 62, she walked across the commencement stage to receive her master’s degree in Asian Studies.

While working on her bachelor’s degree, she had begun interviewing Issei women for a class project on Japanese immigrant clothing in Hawai‘i. The women were in their eighties and early nineties by then and were in relatively good health. Their memories were still sharp, she said.

As they talked about the protective kyahan (leggings) and tesashi (hand and arm protectors) that they wore into the fields every day, and other items such as the kappa (raincoat) and yukata (summer kimono), memories of leaving their families behind in small rural villages in Hiroshima, Yamaguchi, Kumamoto, Fukuoka, Okinawa and other places and sailing to a faraway land slipped into their conversation. They thought Hawai‘i would be their home for only a few years. But the economics of returning home continued to elude them, and once the children started coming, Hawai‘i became home. Picture bride Ushii Nakasone never regretted that. “Hawaii kite yokatta (I’m glad I came to Hawai‘i),” she told Barbara.

The women told Barbara about their early lives with their husbands — men who were strangers to them except for the photograph they held in her hand as they stepped off of the ship in Honolulu. They spoke of the hardship they endured and about trying to make the best of their lives. They even shared intimate stories about their marriage, pregnancy, childbirth, raising children and even birth control.

“The fact that I grew up on the plantation, had experienced similar hardships, was bilingual and had 38 years of professional dressmaking experience made it easier for us to communicate and share intimate stories,” she said.

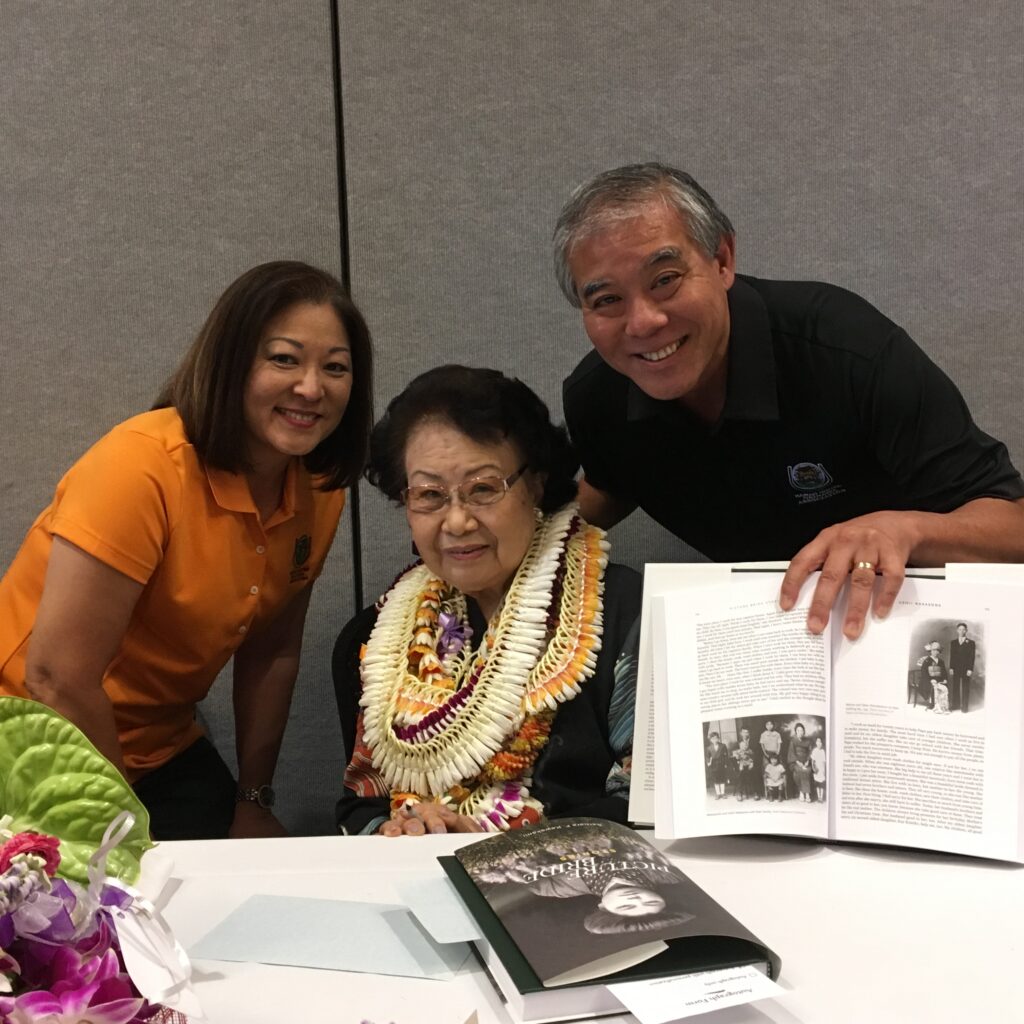

Before she knew it, Barbara had amassed 250 cassette tapes of interviews with the former picture brides. The transcripts of those interviews became the heart of “Picture Bride Stories,” which the University of Hawai‘i Press published in 2016. The 298-page hardcover book features the stories of 16 women whose stories are representative of the more than 21,000 women — 14,000 from Japan and 7,000 from Okinawa (and 1,000 from Korea) — who immigrated to Hawai‘i as picture brides between 1908 and 1924. In telling their stories, Barbara dignified their lives. Their stories are a gift to history, to scholarship and to humanity. Most of all, they are a gift to their families — their grandchildren and the succeeding generations.

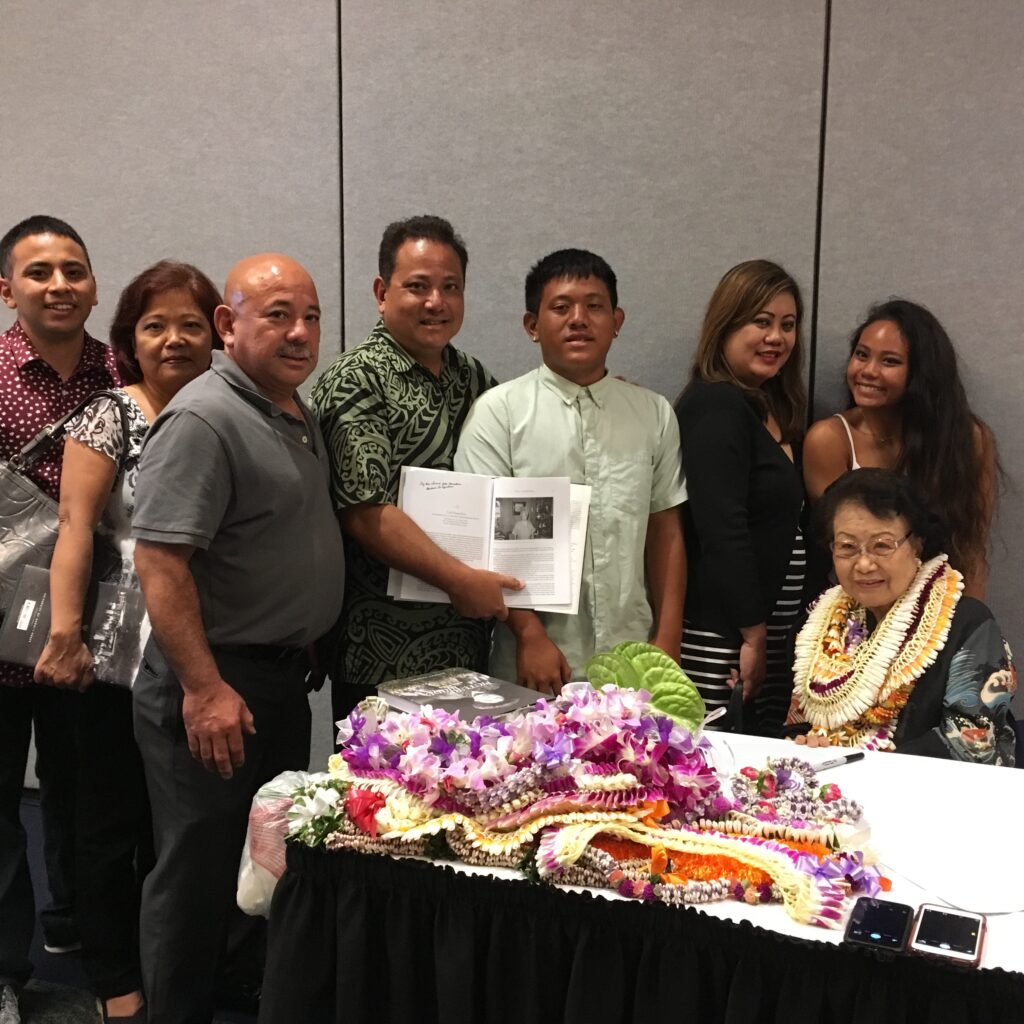

“I had discovered a repository of living treasures — firsthand witnesses to a history that has intrigued me ever since,” Barbara said at the book release reception in 2016. The following year, the Asian/Pacific American Librarians Association recognized Picture Bride Stories with its Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature.

Barbara’s vast knowledge of the picture bride and plantation experience led filmmaker Kayo Hatta to recruit her as a history and costume consultant for Hatta’s 1995 movie, “Picture Bride.”

The women’s stories also inspired University of Hawai‘i music professor Takuma Itoh’s 2019 composition, “Picture Brides (Hawai‘i 1908-1924),” https://youtu.be/ShFaGGD56B for the “American Postcards” series, which told stories from across America. The string quartet, Invoke, performed Itoh’s composition at UH’s Orvis Auditorium. As black and white photos of the picture brides and their husbands and the historical period in which they lived dissolved from one to the next on a screen above the stage, Invoke brought the women’s stories to life in Itoh’s music.

It has been decades since these remarkable women have passed on, but their legacy lives on in their children, grandchildren and succeeding generations, thanks to Barbara Kawakami. “As she documented their stories so they would never be forgotten, she will never be forgotten,” said Allison Arakawa.