Imprisoned Without Due Process

Had the San Times been around on December 7, 1941, when the Japanese Imperial Navy bombed Pearl Harbor, the editors of this publication would likely have been visited by FBI agents at their homes or place of employment, arrested on the spot with little explanation and no due process, detained and interrogated at the U.S. Immigration Station, and kept there in crowded and uncomfortable conditions under military guard until they were transferred to the Sand Island Detention Facility for further processing.

Their worried, fearful and now fractured families would have no idea where they were or why they were taken away so abruptly. The communities they served would be without the trusted voices they had come to rely upon for news, information and opinion. And perhaps worst of all, they would be treated like enemy aliens, even though their loyalties were unquestionably to the United States.

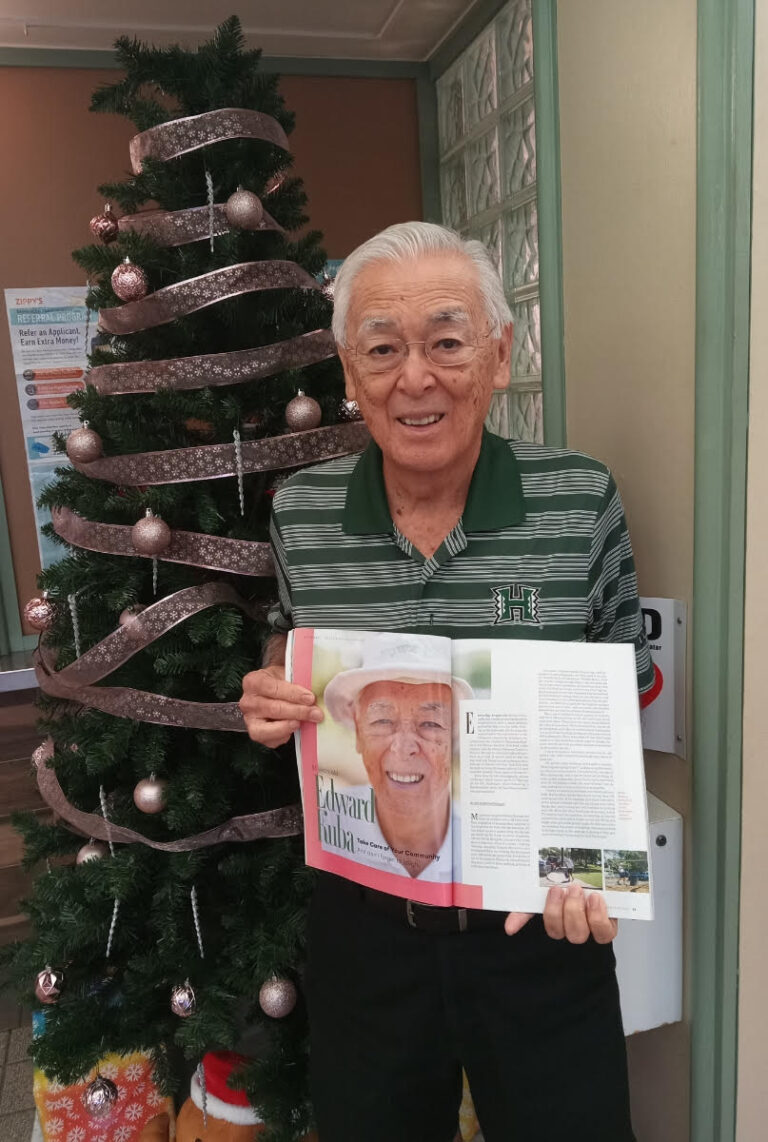

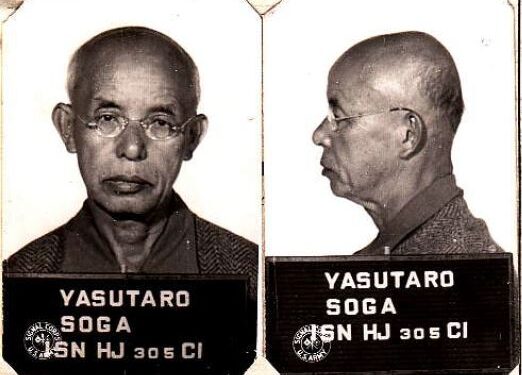

We know this is what would likely have happened to them because it actually did happen to a number of journalists whose publications appealed to the ethnic Japanese community in Hawaiʻi, people like 68-year-old Yasutaro Soga, editor and publisher of the Nippu Jiji newspaper. After his arrest, Soga spent the next four years being shuttled from one American detention facility or concentration camp to another. Soga’s profession and standing in the Japanese community – along with his racial background – marked him as dangerous in the eyes of the military government that ruled Hawaiʻi from December 7, 1941 to October 24, 1944.

Soga published a memoir about this dark time in both his personal life and in U.S. and Hawaiʻi history and called it “Tessaku Seikatsu” (“Life Behind Barbed Wire”) in which he described being arrested at his home and taken away like a criminal, leaving behind an understandably distressed but stoic wife whom he would not see again for six months. Although what happened to Soga happened to others in Hawaiʻi – people identified as holding leadership or influential positions in the ethnic Japanese community in the Islands – what distinguished Soga was his extensive and detailed first-hand account of his personal experiences while in detention first published in 1948, and then later translated from Japanese into English by a team at the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaiʻi and published by the University of Hawaiʻi Press in 2008.

It is not clear exactly how many people from Hawaiʻi were interned during World War II. Some were held for shorter periods of time and then released. Others, like Soga, spent most of the war imprisoned. During the first two days after Pearl Harbor, 391 people of Japanese ancestry were arrested. It is widely believed by historians today that a pre-existing list compiled years before the attack must have been used to identify such a large number of people so quickly. They included religious leaders (e.g., Shinto, Buddhist and Christian ministers), Japanese-language teachers, businessmen, kibei (Americans of Japanese ancestry who spent a significant portion of their youth in Japan) and volunteer consular agents who helped their friends and neighbors register important events such as births and deaths with the local Japanese consulate office. As time went on, hundreds and hundreds more were arrested and imprisoned.

For decades after the war ended these stories of the Hawaiʻi internees were not well known. Perhaps the former internees just wanted to get on with their lives and tried to put their past behind them, or perhaps they did not want younger generations to have to carry the psychological burden of this past trauma into their futures. Because in Hawaiʻi the imprisonments were selective, not en masse as on the continent where 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry were relocated and imprisoned in concentration camps as the result of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, there was likely also a greater social stigma in Hawaiʻi to having been one of those arrested and imprisoned. While today we know the entire process both in Hawaiʻi and on the continent was unjust and unconstitutional, back in the early 1940s sentiments may have been more mixed. Even within the Japanese community in Hawaiʻi, there are stories of individuals who wanted to avoid being seen cavorting in the open with former internees and only visiting them under cover of darkness. Not only did the former internees have to live with the humiliation of being imprisoned like criminals during the War, but many chose to suffer in silence after their release to avoid calling attention to their wrongful imprisonment. Remarkably, even their descendants may have not known what happened until the stories of Hawaiʻi incarceration began to resurface.

Uncovering the Ugly Truths of Our Past

For a period in the 1980s, the stories of Hawaiʻi internees began to resurface as part of the nationwide effort by the Commission of Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, directed by the United States Congress, to examine the facts and circumstances surrounding this period in history. It was an opportunity for those who had been wrongly incarcerated decades earlier to finally speak what was on their minds and express what they had kept holed up inside for so long. The findings and conclusions of the Commission resulted in a 467-page report called “Personal Justice Denied” released in 1983.

In short, the report concluded that Executive Order 9066, which permitted the relocation and internment of people of Japanese ancestry, was “not justified by military necessity, and the decisions which followed from it—exclusion, detention, the ending of detention and the ending of exclusion—were not founded upon military conditions.”

Race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership were found to be the reasons for the internment and that a “grave personal injustice was done. . . without individual review or any probative evidence.”

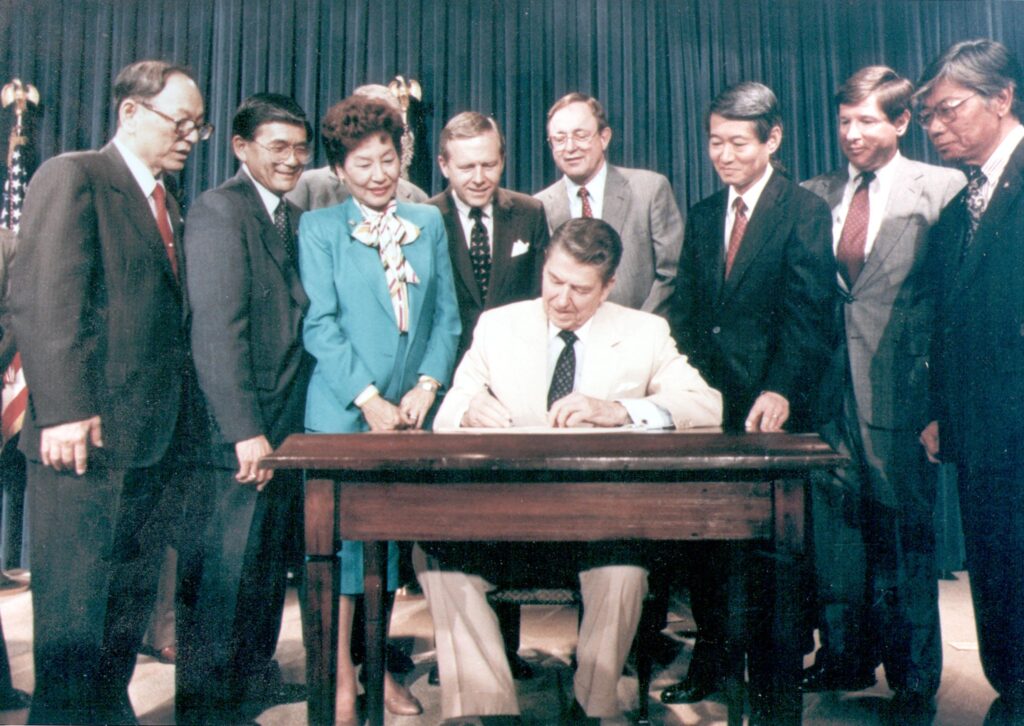

In 1988, the 100th Congress adopted H.R. 442, which became the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 and conveyed a monetary reparation of $20,000 and a public apology to the surviving former internees. Sadly by this time, many had already passed away. For those who lost their homes, livelihoods, dignity and freedoms, this amount was a token gesture, but for many it was nonetheless meaningful to have the government admit that their incarceration was unconstitutional and to apologize for it.

Re-Discovering the Honouliuli Internment Camp

The passage of time has a way of erasing historical wrongs if they are not talked about and remembered, and for many decades, the wrongs committed against some 2,000 residents of Japanese ancestry in Hawaiʻi were sort of known by some and not by others. And that’s the way things could have remained in perpetuity had it not been for a growing number of community voices in the present that spoke up – loud and clear – about the injustices of the past.

Perhaps the ripple that eventually generated a tsunami of interest in Hawaiʻi’s internment history was a phone call to the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaiʻi by a local news station in 1998. The caller wanted to know where Oʻahu’s internment camp was located during World War II. The station was planning to air a story about this historic site to coincide with the broadcast of the movie, “Schindler’s List.” The problem was that no one knew exactly where the Oʻahu internment camp was located, but the question launched a years-long mission involving a diverse group of people to find the answer.

Mission Possible!

The Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaiʻi, in particular, took a leading role in re-discovering Honouliuli using historical photographs, documents, archaeological evidence, maps, oral histories and by tapping into the memories of longtime area farmers who recognized features from photographs such as a distinctive-looking aqueduct that is still identifiable today. But all of this was no easy task. Foliage had grown over most of the site, obscuring what little remained of the combined civilian internment and POW camp. Most of the structures had been torn down. But bits and pieces began to emerge, often thanks to the trained eyes and hands of archaeological experts.

Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii volunteer staff associates Betsy Young (middle) and Jane Kurahara (right) show a visitor a historic photo at the Honouliuli National Site. (Photo courtesy of National Park Service)

The internment and POW camp was located on 160 acres of land on west Oahu in a gulch that was secluded and hot. When rediscovered it was on land owned by agribusiness giant Monsanto, which later donated the land to the National Park Service. UH West Oʻahu owns an adjacent property, which made the site ideal for UH West Oʻahu students to practice their archaeological field work.

Archaeologists Jeff Burton and Mary Farrell who had experience studying Japanese American internment camps on the continent, came to Hawaiʻi in 2006 to build upon what little information already existed about detention sites throughout the state on most if not all the inhabited islands. Their meticulous research documented where these places were located and what remained of them, if anything. Sometimes all that existed were concrete slabs or the foundation for a guard tower. In other cases, structures were intact but repurposed for other contemporary uses unrelated to their wartime functions. In total, there were about 13 detention sites identified and documented.

In ensuing years, JCCH staff and volunteers, researchers, university students, community members, and others have helped identify a wide assortment of artifacts and features at Honouliuli, the largest and longest-running of the detention or internment sites in Hawaiʻi. Collectively they have helped piece together a fuller picture of Honouliuli with the guidance of historical site professionals after years of expeditions, community work days, documents research, and interviews with the few remaining survivors of the internment camp or their family members.

Honouliuli Named a National Monument

The culmination of many years of sustained tireless research came in February 2015 when then-President Barack Obama declared Honouliuli a national monument by presidential proclamation. In his proclamation, President Obama wrote: “The Honouliuli Internment Camp (Honouliuli) serves as a powerful reminder of the need to protect civil liberties in times of conflict, and the effects of martial law on civil society. Honouliuli is nationally significant for its central role during World War II as an internment site for a population that included American citizens, resident immigrants, other civilians, enemy soldiers, and labor conscripts co-located by the U.S. military for internment or detention.”

It was a monumental achievement for all those who worked so hard to ensure that Honouliuli – and by extension Hawaiʻi’s other detention or internment sites – would not be forgotten and that their enduring lessons would resonate far into the future through remembrance activities and education.

Tenth Anniversary Celebration

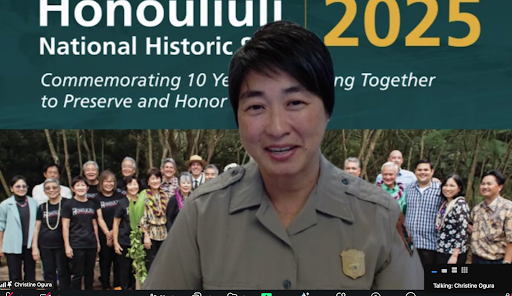

It has been 10 years since Honouliuli was declared a national monument, and the National Park Service’s Christine Ogura, permanent superintendent of the Honouliuli National Site, recently announced commemorative events throughout the year.

“The park and over 55 partners will honor and preserve this history by featuring different aspects of the park — past, present, and future — to connect and engage the community to this history,” Ogura said in a news release. “The park tells the story of incarceration, martial law, and prisoners of war in Hawaiʻi during World War II. The incarceration site, opened in 1943, was the largest and longest used incarceration site in Hawaiʻi where U.S. residents and citizens of Japanese and European ancestry were unjustly detained. The camp also held over 4,000 prisoners of war including Okinawans, Koreans, Japanese, and Italians.”

Events and activities will be both virtual and in-person and includes “a speaker series, special tours, book events, pop-up exhibits, film screenings, panel sessions, musical performances, youth and school initiatives, and a statewide art exhibit. Many events will be free through the park’s partnership with its non-profit organization, Pacific Historic Parks.” Note that physical access to the Honouliuli site is currently restricted as there is no public right-of-way directly to the site. Ogura is listening to the community’s ideas and proposals for developing the site for future use.

For a calendar of upcoming activities and events, as well as for more details about the former internment camp, please visit the Honouliuli Historic Site’s website at https://www.nps.gov/hono/index.htm.

Lessons from History for Today’s World

Those interested in learning more about Hawaiʻi’s internment history have considerably more resources to turn to today than even a decade ago thanks to a number of esteemed researchers, authors and filmmakers who have focused their literary and cinematic lens on Hawaiʻi’s internment history. These include Tom Coffman’s “Inclusion: How Hawaiʻi Protected Japanese Americans from Mass Internment, Transformed Itself, and Changed America” (University of Hawaiʻi Press); Gail Okawa’s, “Remembering Our Grandfather’s Exile: US Imprisonment of Hawai‘i’s Japanese in World War II” (University of Hawaiʻi Press); Gail Honda’s “Family Torn Apart: The Internment Story of the Otokichi Muin Ozaki Family” (Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaiʻi); “Claire Sato and Violet Harada’s (eds) “A Resilient Spirit: The Voice of Hawai‘i’s Internees” (Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaiʻi); Suzanne Falgout and Linda Nishigaya’s (eds) “Breaking the Silence: Lessons of Democracy and Social Justice from the World War II Honouliuli Internment and POW Camp in Hawai‘i (University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa); and Mary M. Farrell’s “Honouliuli POW and Internment Camp: Archaeological Investigations at Jigoku-Dani 2006-2017” and “Dark Clouds Over Paradise: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Confinement Sites in Hawai‘i” (Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaiʻi). Yasutaro Soga’s seminal work, “Life Behind Barbed Wire: The World War II Internment Memoirs of a Hawai’i Issei” (University of Hawaiʻi Press) is also available.

As for videos on the topic, search YouTube for “Honouliuli internment camp.” There are many video clips related to the Honouliuli internment camp as well as some documentaries such as “The Untold Story: Internment of Japanese Americans in Hawaiʻi” and “Voices Behind Barbed Wire.”

At the end of “The Untold Story” documentary, U.S. Senator Daniel Inouye makes an appearance. “There are some who say, well, why talk about it?” Hawaiʻi’s then-senior senator says about the Islands’ incarceration history. “I think we should. If only to remind ourselves that this can happen in our democracy if we’re not vigilante. Because it did.”

Kevin Y. Kawamoto is a former associate professor at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and

currently works at the UH Mānoa Center on Aging. He has written or co-written a number of

academic textbooks and has been a freelance writer for more than 30 years.