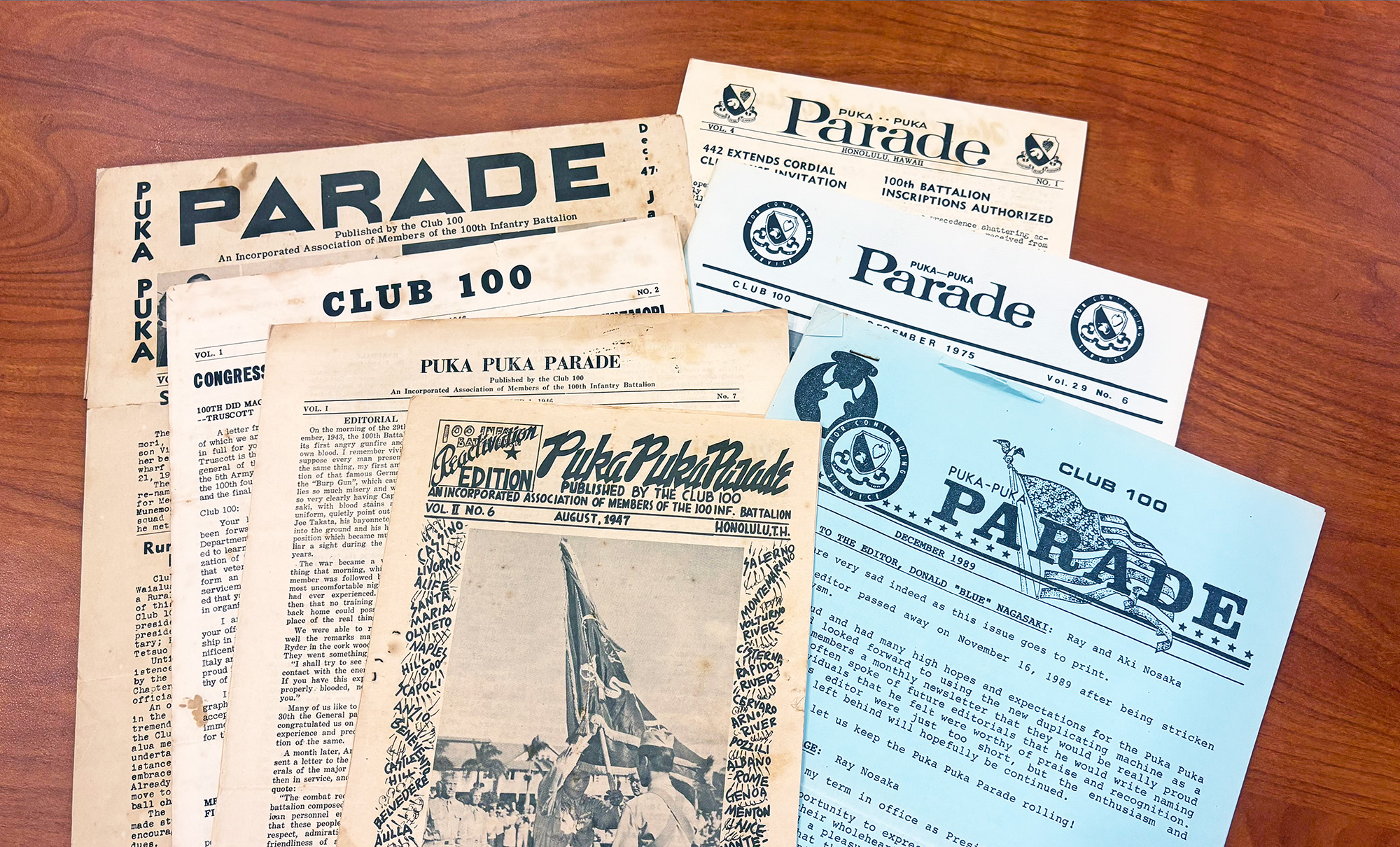

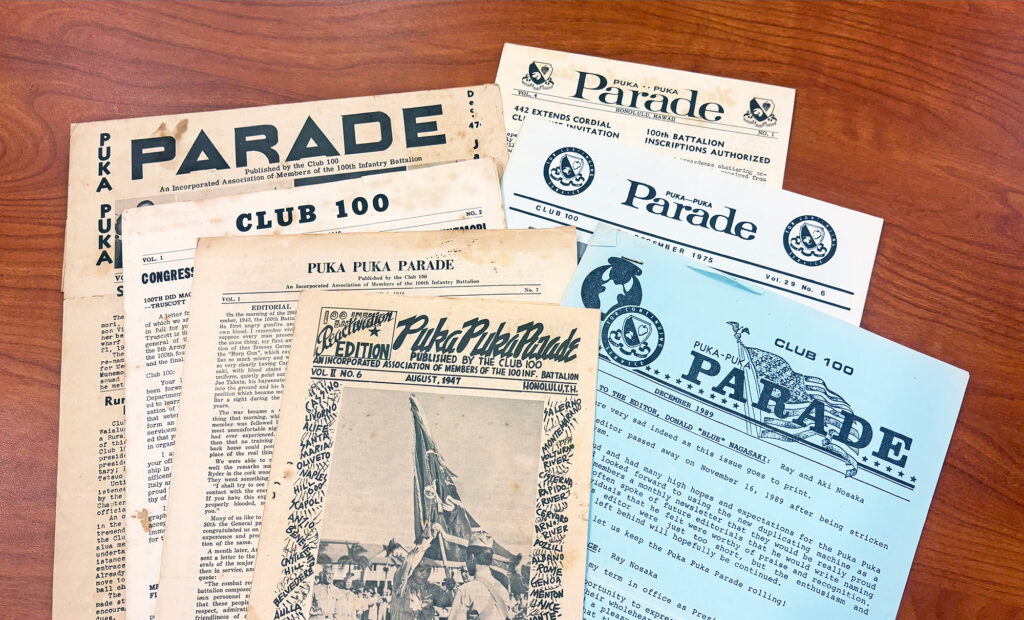

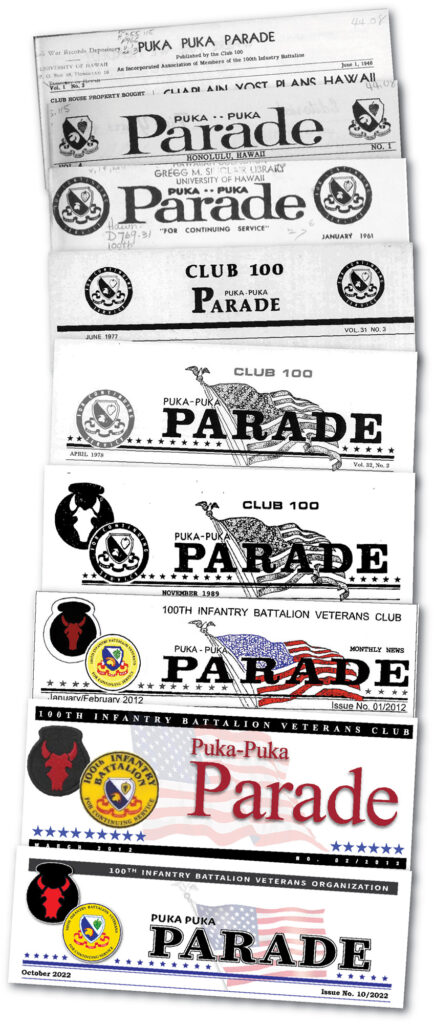

The “Vol. 80” that appears under the Page 1 banner of the 100th Infantry Battalion veterans club newsletter, Puka Puka Parade, is a testament to camaraderie, longevity and dedication. This year marks 80 years since the veterans club, known to many in Hawai‘i as Club 100, began publishing its monthly newsletter, Puka Puka Parade — PPP, for short.

Volume 1, Issue 1, was published in April 1946, four months after Club 100 was incorporated in December 1945 in what was then the Territory of Hawai‘i and nearly a year after victory had been declared in Europe in World War II. The first issue was a modest four-pager with single-spaced text that ran across the pages.

The history of the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate) dates back to June of 1942 when the 1,432-member unit made up primarily of Americans of Japanese ancestry from across Hawai‘i sailed out of Honolulu Harbor aboard the S.S. Maui as the Hawaiian Provisional Infantry Battalion. Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor only six months earlier. After zigzagging across the Pacific Ocean for a week, the Maui arrived in Oakland, Calif., on June 12, when it was renamed the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate) — “Separate” meant it was not attached to any unit. The 100th Battalion was transported to Camp McCoy, Wis., where the island boys underwent six months of training and played in the snow for the first time in their lives. In early January of 1943, the 100th Battalion headed south for more training at Camp Shelby, Miss., and then to Louisiana, where they performed maneuvers at Camp Claiborne.

The battalion finally shipped out to Algeria, North Africa, in early September. The Fifth Army Command had planned to use the 100th soldiers to guard supply trains — an assignment Lt. Col. Farrant Turner, the 100th Battalion’s commanding officer, and the soldiers themselves rejected. They had trained hard to fight for America, not to guard supply trains.

Their argument was heard and the 100th was subsequently attached to the 34th “Red Bull” Infantry Division of the Minnesota National Guard. The 34th had been the first American division deployed to Europe in World War II.

The 100th Battalion landed at Salerno, Italy, on Sept. 22, 1943, and entered combat four days later. They were the first Japanese Americans to fight in Europe. The One Puka Puka lost its first two men, Sgt. Shigeo Joe Takata and Pvt. Keichi Tanaka, a week later when they were killed in action within an hour of each other.

The more than a year that the 100th Battalion soldiers trained together bonded them as brothers in arms. Within months of arriving at Camp McCoy, the One Puka Puka soldiers began contributing $2 from their monthly pay toward a future clubhouse back home in Hawai‘i. More than three hundred 100th Battalion soldiers never lived to see their clubhouse.

“As the years rolled by and the battalion moved farther and farther away from Hawai‘i, the clubhouse became more than a dream. We planned it and talked about it and saved for it,” wrote Able Company veteran Sam Sakamoto in the club’s inaugural newsletter in 1946.

With the 100th Battalion always on the move in Europe, the decision was made to send the clubhouse funds to Charles R. Hemenway for safekeeping until the men returned from the war. Hemenway was a prominent business and community leader in Hawai‘i and was among the first three honorary members voted into the 100th Battalion in September 1944 while fighting near Naples, Italy.

In an article in the first Puka Puka Parade, Sakamoto noted that most of the veterans had contributed approximately $60 of their pay to the clubhouse by the time they returned from the war. They envisioned a clubhouse where they could bring their families for club activities and celebrations. It would have a bar, a bowling alley, Ping-Pong tables, a pavilion for dancing, rooms for “bull sessions” and even a bed for a nap. The bowling alley never materialized, but the veterans made good use of the smooth Turner Hall (named for Col. Farrant Turner) floor for ballroom dancing. The One Puka Puka veterans’ dream clubhouse was finally built in 1952 and dedicated to the 100th boys who died in the war.

The club’s inaugural newsletter was aspirational. Sam Sakamoto shared his hope for “bigger and better issues” that the members would help to produce. He said Headquarters Chapter veteran Keichi Kimura, who became an artist after the war, would be asked to design the newsletter’s banner. With photos, “it is hoped a dressy bulletin will make a regular appearance.”

But first the newsletter needed an identity. The club’s executive council voted to award a prize of $10 to the member submitting the winning name for the newsletter. By June, a panel of judges had selected Maui veteran Arthur Itsuo Shinyama’s suggestion of “Puka Puka” as the newsletter’s name. Well, almost … Shinyama had derived his nomination from the battalion’s “One Puka Puka” moniker. The judges felt that “Puka Puka” was incomplete, so they considered several additions to complete the name, among them, “Bulletin,” “News” and “Monthly,” before finally settling on “Parade” because of its military connotation. With that, Puka Puka Parade became the voice of the 100th Infantry Battalion and Club 100.

It was hoped that each “company” — “chapter” in the Club 100 structure —would submit a monthly column about its activities and members. “Let us know who’s getting married or who’s passing out cigars,” wrote Sakamoto. “And if you’re going into business, we certainly will be able to give you some free publicity in these columns.” He noted also that Dog Chapter member and future U.S. senator from Hawai‘i Spark Matsunaga planned to share information about surplus property and that Headquarters Chapter member Kenichi Suehiro, who had gone to work for the Veterans Administration, offered to pen a monthly column about veterans affairs and benefits.

In a separate article titled, “Keep Businesses in the 100th,” Suehiro urged the members to patronize businesses run by 100th Battalion veterans. “Do you know that you can get practically all services to make life bearable — from a haircut to buying a car or home and their upkeep and insurance for them — and still contact only members of the 100th Club?” he wrote. Since returning from the war, the members had found careers in a variety of fields, including construction, automotive businesses, insurance and retailing. “We’d like to keep a business index so as to know what businesses all the fellows are in. Perhaps we can throw a little business your way every now and then,” suggested Suehiro.

In a few paragraphs every month, the war veteran “reporters” summed up the goings-on in their respective chapters. They reported on attendance at their chapter meeting and the snacks the members had enjoyed. The columns also included information about vacations members and their families had taken, graduations, weddings, births and other achievements. And, as the years passed, they said goodbye to their wartime buddies in the pages of the Puka Puka Parade.

Club 100 “daughter” Drusilla Tanaka remembers her father, Bernard Akamine, writing his Baker Chapter column, pecking away intently on an old manual typewriter using only his index finger.

The Puka Puka Parade issues contain valuable historical information about the battalion and its postwar years as Club 100, much of it written by the veterans themselves, said Susan Muroshige Omura in a July 6, 2012, Hawai‘i Herald feature. Omura’s father, Kenneth Muroshige, served in Baker Company during the war. She has overseen the club’s Education Center website (https://www.100thbattalion.org/) for many years. “The PPPs are primary source material, so they are important to preserve for researchers,” said Omura. The complete collection of Puka Puka Parade issues can be accessed through the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s Hamilton Library website: https://hdl.handle.net/10524/11835.

The Puka Puka Parade was printed in a booklet format for many years. In 1989, the club began printing the PPP in-house on 8.5-by-14-inch paper. The first and last pages were printed on a paper shade known as “Infantry Blue,” said Drusilla Tanaka, the club’s executive secretary from 1995 to 2000. It was one of many official colored papers that the Army used. “The veterans liked it because it was easy to find in their house,” she said. It was also easy to find in office supply stores. Tanaka said the 100th Battalion’s Kamoku Street clubhouse is also painted in “Infantry Blue.”

After the newsletter was printed, the veterans, and usually their wives and oftentimes other family members, would gather at the clubhouse to collate, staple and fold the issue. Tanaka believes the “collating days” helped to cement the relationships between the Nisei veterans and their wives and the Sansei descendants. If Tanaka’s mother, Jeanette Akamine, was off from work, she joined her husband Bernard to help collate the PPP. “[It was] like being in Grand Central Station — with so many [people] coming and going, and more time spent socializing than actually working,” Jeanette Akamine joked.

“In those days, it was so helpful to have retired USPS (U.S. Postal Service) workers like Joe Muramatsu; Alfred Arakaki, his brother Pluto; and Kuni Fujimoto overseeing the sorting and binding with rubber bands,” said Tanaka. While getting the boxes and bags ready to take to the post office, she noticed that the clubhouse had grown quiet. The volunteers had retired to the lounge and gotten a head start on reading their copy of the Puka Puka Parade while enjoying some refreshments.

The “Infantry Blue” Puka Puka Parade was retired in 2010 and replaced with a newsletter printed on 11-by-17-inch white paper by a commercial printer. The flat sheets were brought to the clubhouse, where the veterans, some in their 90s by then, and other volunteers gathered to manually collate and fold the sheets. They worked quietly and diligently, using small wooden blocks to flatten the folds into 5.5-by-8.5-inch rectangles. Other volunteers attached preprinted adhesive address labels to each newsletter. An efficiency expert would declare the operation “grossly inefficient.” But the “expert” would not have understood how it connected the veterans from the various chapters with other volunteers. “While historians may credit the friendships forged in combat, my father would say that it was the veterans working together on the annual lü‘au, building the clubhouse and working on fundraisers that created lasting friendships,” said Tanaka.

As the veterans began to pass, their wives and other family members filled their shoes as chapter reporters, continuing to give the 100th Battalion a voice through the PPP.

Today’s Puka Puka Parade is a totally digital effort directed by the club’s office manager, Amy Kwong, the Yonsei granddaughter of Able Company veteran Eugene Kawakami. As the PPP’s volunteer editor, she plans, designs and distributes each month’s issue. All of the “reporters” today are 100th Infantry Battalion descendants.

When most of the issue is laid out, Kwong emails her draft InDesign layout to a team of volunteer proofreaders, also members of the 100th Battalion ‘ohana, who help move the production along. When the issue is ready for distribution, Kwong emails the issue, usually 16 pages, to nearly a thousand Club 100 Lifetime members and non-member friends. About 200 black-and-white copies printed in a booklet format are also mailed to members who prefer to read a paper copy.

Club 100 and the Puka Puka Parade were important to Kwong’s grandparents, Eugene and Gladys Kawakami. “We literally brought my grandpa to turn in his last golf news article at the clubhouse before taking him in for the heart surgery that ended his life,” Kwong recalled. “He was writing for PPP until the very end of his life.”

His dedication inspires her to this day. “The PPP has a very special place in my heart and I am deeply thankful to the past PPP editors, as well as to both past and current team members, for their dedication, love and hard work in keeping this publication alive for 80 years.”

From a humble Volume 1 Puka Puka Parade typed on a clickety-clack manual typewriter in 1946 to the silence of today’s totally digital Volume 80 eight decades later … the dedication to keeping the legacy of the 100th Infantry Battalion soldiers who fought for America in World War II endures in the pages of the Puka Puka Parade.

In April 2020, Karleen Chinen retired as the Editor of The Hawai‘i Herald after 16 years of leading the semimonthly publication that covers Hawai‘i’s Japanese American community. Her book, Born Again Uchinanchu: Celebrating Hawai‘i’s Chibariyo! Story, chronicling Hawai‘i’s Okinawan community from 1980 to 2000. Chinen previously served as a consultant to the Japanese American National Museum and was part of the JANM team that took its traveling exhibition, From Bento to Mixed Plate: Americans of Japanese Ancestry in Multicultural Hawai‘i, throughout the neighbor islands of Hawai‘i and to Okinawa for its international debut in November 2000.